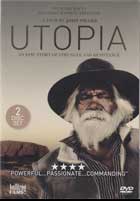

Utopia: An Epic Story of Struggle and Resistance 2013

Distributed by Bullfrog Films, PO Box 149, Oley, PA 19547; 800-543-FROG (3764)

Produced by John Pilger

Directed by John Pilger and Alan Lowery

DVD, color, 112 min. (280 minutes extras)

College - General Adult

Human Rights, Indigenous Peoples, Racism

Date Entered: 06/03/2015

Reviewed by Wendy Highby, University of Northern ColoradoIn Utopia: An Epic Story of Struggle and Resistance, investigative journalist and documentarian John Pilger and co-director Alan Lowery deliver a searing critique of Australia’s treatment of its Aboriginal First People. Ironically counter to the film’s title, Australia is exposed as harboring a dystopic system of racial apartheid. Utopia reveals that racist attitudes toward the First Nation People are ubiquitous and entrenched, endemic not only in neoliberal policies, but rampant in mainstream Australian culture. The documentary is indeed epic in its scope, covering the historical, political, and sociological aspects of Australia’s racial apartheid. It focuses upon events occurring in the past three decades, paying particular attention to two relatively recent examples of intrusively racist government action (the result of a “moral panic” brought on by sensational media’s false accusations of pedophilia) the 2007 “intervention” in which the army was deployed to occupy the Northern Territory, and the 2009 forced removal of 37 Aboriginal children from their families in New South Wales.

The filmmakers’ thorough journalistic treatment provides a sobering catalog of the deplorable social conditions endured by Aborigines and injustices perpetrated upon them: low quality of life indicators, high incarceration rates, rising suicide rates, incidences of police brutality and misconduct, greedy land and resource grabs, and governmental bureaucracy and mismanagement. The documentary resurrects and fills in suppressed and denied history; it confronts the delusional denials of the 1990s “history wars,” condemns the lack of an appropriate memorial at the site of the Rottnest Island internment camp, and reminds viewers of a legacy of labor protests evidencing Aboriginal resistance. The film is distinctive because it includes Aboriginal voices, does not shirk nuance and complexity, and seeks real solutions. Causality is probed, logical dots are connected. The film is an amalgam of investigative journalism, ethnographic interview, academic analysis, and political advocacy. Pilger’s sympathies lie with the Aborigines and run counter to the neoliberal party line; he holds government officials’ feet to the fire, demanding accountability for the failure of governmental policies.

Utopia is a two-disc set; the featured documentary is 112 minutes (divided into 24 chapters) and 280 minutes of supplementary materials are included, including ten extended interviews: six feature Aboriginal activists, two journalists, one an environmentalist and extractive industry expert, and the final an anthropologist. In several of the interviews, the seemingly benign idea of assimilation is deconstructed and discredited. The interviewees explain that behind it lurks a culturally genocidal attitude that demands the performance of a self-negating disappearing act by Aboriginal people, white culture being the norm to which all must adhere. The pressure to assimilate springs from an intolerance of differences and belief in the inferiority of the minority culture. The production’s extended interviews and chapter divisions will easily lend themselves to targeted classroom use. The film would support curriculum in anthropology, ethnic studies, policy studies, political science, and sociology. Students of history, human rights, area studies, environmental studies, and journalism will also benefit.

Like the tones of the didgeridoo music in its introduction, the film’s content continues to reverberate in this viewer’s psyche. I continue to be awed by the tenacious hope evident in Aboriginal advocate Rosalie Kunoth-Monks’ expression of the humanitarian starting points needed to begin healing and reconciliation: a recognition of the sovereignty of the First People, diplomatic talks, and treaty negotiation. She lists their priorities: rights to land, language and access to knowledge. I can still sense the palpable frustration expressed in anthropologist Jon Altman’s wish for external, international mediation to help Australia begin an honest reconciliation process. And finally, I am ashamed of my ignorance but grateful for the honesty of Patricia Morton Thomas, an Aboriginal writer, actor, and filmmaker. In her interview she confessed her weariness of educating whites ignorant of her culture; she urges us to be less lazy and more intellectually curious: “look, we are the most written-about people in the entire world; get off your butt, go down to your library and find a book.” Of course initially, I didn’t think this applied to me, a well-read librarian. But when Rosalie Kunoth-Monks mentioned she gained the right to vote in 1967, I had to admit I had no idea when Native Americans in the United States gained suffrage. This impelled me to research and learn that in the U.S.A., even after the 1924 passage of the Snyder Act, it took almost forty years for all fifty states to grant suffrage to Native Americans. Thus, I have a final recommendation, stemming from personal experience: the film could serve as a consciousness-raising tool for whites and a point of reference with which to compare other countries’ treatment of their indigenous people.