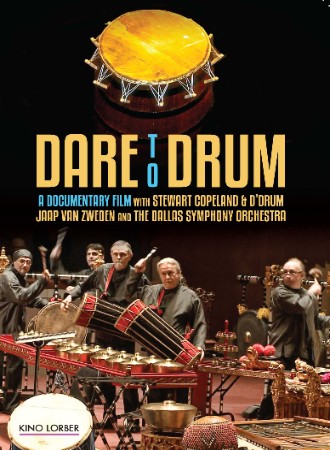

Dare to Drum 2015

Distributed by Ten Ears Productions, 1434 Sereno Dr., Dallas, TX 75218

Produced by John Bryant

Directed by John Bryant

DVD , color, 85 min.

Middle School - General Adult

Music, Stewart Copeland, D’Drum, Jaap van Zweden, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Percussion, Gamelan Music

Date Entered: 10/27/2015

Reviewed by Vincent J. Novara, Curator, Special Collections in Performing Arts, University of MarylandThis documentary does not include a complete performance of the musical composition in study – not in the film proper, nor as a bonus feature. After the viewer invests 85 minutes to an inspiring tale about the development, collaboration, staging, and performance of a new work that is deemed worth a documentary, all that is provided of the final composition is a series of excerpts. Granted, there is generous footage of the work in progress and rehearsals, but there is currently no means to experience the composition in its entirety. Alas, until some means to hear or see a compete performance of the work, the ultimate usefulness of such a documentary can be judged on this omission alone. One does get to witness nearly the whole creative process lifecycle, but there is not enough presented of the result. For all we know, the result could be terrible music that does not warrant future programming or serious study. (And consider the annoyance felt right now after reading the introductory paragraph of a film review and not finding a single name or title – that is the frustration created by such major omissions.)

Of course, filmmaker/percussionist John Bryant is due a break in this regard as there are extensive rights issues, and other restrictions pertaining to unions, that render such performance documentation extremely expensive, if not impossible, but without any supporting audio or video of the composition, this documentary feels incomplete. When the featured composer, Stewart Copeland, states that “the journey is the event” when describing the creative process, that could equally apply to Dare to Drum.

The film chronicles from germination to debut the 2007 commission by the Dallas Symphony of a new composition by Copeland, Gamelan D’Drum, which features Dallas-based percussion group D’Drum. The five-member “drum band” consists of academics and orchestral musicians (two with Dallas Symphony), each bringing different strengths to the ensemble across a wide range of western and non-western percussion traditions, but presented here as unified around an interest in the Gamelan instruments from Indonesia. (Bryant is also a member.) Copeland is best known as the highly influential drummer of The Police, originally a late-1970s punk band that transitioned to pop and art rock as they continued into the mid-1980s. The Police sold tens of millions of records, toured the world several times, and are documented in multiple concert films, as well as in television and festival appearances. Copeland also established a decades-spanning career as a composer scoring films and creating new works for ballet and opera. Throughout Dare to Drum, his gesticulations and outsized personality (see regrettable statements like “Gamelan is sexy!”) are viewed in sharp contrast to the subtle Texas charm of the D’Drum members, and the earnest, yet at times stoic, Dallas conductor, Jaap van Zweden.

Until the appearance of van Zweden, much of the commentary is not exceptionally profound, and is presented a bit too clipped, or too edited. The members of D’Drum are clearly very intelligent and possess great knowledge about percussion, but they are not given many opportunities to speak to any depth about these topics, and instead contribute to what comes across as a string of sound bites. Copeland, however, is afforded the opportunity to expound on his compositional method, as well as on many theories for the history and role of percussion (and male percussionists).

John Bryant assembles Dare to Drum from a visually informative assortment of material. The interviews occur on each location where the project is developing, placing the viewer in the moment with the unfolding creative process. There is very enjoyable performance footage of D’Drum, notably in collaboration with Copeland revealing how performative considerations influenced the compositional process. There is also excellent contextual historic footage of indigenous performers of the non-western instruments used by D’Drum, including where instruments originate, how they are handcrafted, and their function in ritual and community. Bryant does not let the film get lost in jargon or technical details, and it should appeal to any audience with an appreciation for percussion music. Dare to Drum peaks during the fantastic rehearsal footage with van Zweden. His rehearsal technique is on clear display; particularly when witnessing van Zweden nuancing the balance considerations of a sizable percussion ensemble accompanied by orchestra.

Following the excerpted footage of the Gamelan D’Drum debut concert, Bryant attempts in the concluding segments to tie together the documentary with the notion of drumming brotherhood. While this resonates with Copeland’s earlier assertion that “drummers are much more tribal and they’re not threatened by each other… [a drummer] feels empowered by all the other rhythms going on,” it falls flat when presented as a concluding thought. Ultimately, this is a documentary about a creative process. Public libraries situated in communities interested in world music and multiculturalism will do well to acquire this title, as will academic music libraries supporting percussion programs that integrate western and non-western instruments and techniques. Otherwise, it is not essential for media collections – especially until a complete performance is available to best comprehend the product of this collaboration.