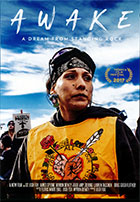

Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock 2017

Distributed by Bullfrog Films, PO Box 149, Oley, PA 19547; 800-543-FROG (3764)

Produced by Kyle Cadotte, Josh Fox, Doug Good Feather, Teena Pugliese, Deia Schlosberg

Directed by Myron Dewey, Josh Fox, James Spione

DVD, color, 89 min.

High School - General Adult

Activism, Constitutional Rights, Environmental Movement, Indigenous Peoples, Law Enforcement, Native Americans, Water

Date Entered: 01/19/2018

Reviewed by Wendy Highby, University of Northern ColoradoAwake: A Dream from Standing Rock documents the rise of the “#NODAPL” protest movement in 2016. This grassroots indigenous environmental movement non-violently resisted the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) by Texas-based developer Energy Transfer Partners. The movement’s geographic epicenter was an encampment called “Oceti Sakowin” located in Norton County, North Dakota, atop the Bakken shale formation in the Williston Basin. The DAPL transports oil extracted through the process of hydraulic fracturing (commonly known as “fracking”) from the Bakken oil fields to the State of Illinois; in North Dakota it is routed under the Missouri River, through sacred sites, and within half mile of sovereign land of the Standing Rock Sioux. Members of the movement share a common perception that “Water is Life” and call themselves “Water Protectors.” They deem their movement essential for protection of the Missouri River watershed and they connect this to the larger issues of climate change and environmental health of the entire planet.

The film is a collaborative effort between native film director Myron Dewey, writer Floris White Bull, and non-native filmmakers Josh Fox (Gasland) and James Spione (Incident in New Baghdad). It presents the pro-environmental, anti-DAPL perspective of the #NODAPL multi-tribal gathering of American Indians in three parts and a coda. Fox directed Awake, the first part of the triptych, written by White Bull; Spione directed Backwater Bridge, the second; and Dewey directed the final episode, Standing Rock through Indigenous Eyes. The documentary begins with Floris White Bull recounting a vision that inspired her to become a Water Protector; she connects her personal intuitions to the collective prophesy of an ominously destructive black snake. The narrative explains why activists were drawn to a remote encampment on the North Dakota prairie, willing to camp out in harsh conditions, brave exposure to extreme weather, and endure negative responses to their resistance. The piece centers upon the failure of police-community relations, the alleged violation of constitutional rights, and the profoundly spiritual human impulses toward justice, connection, and healing. While the film contains some footage of quotidian life in camp, it shows little of the meeting- and conversation-intensive process of group consensus-building, the bread and butter of political organizing. It hints at Native Americans’ economic woes and challenging social conditions, declaring the encampment’s subsistence level existence better than homelessness.

The greatest proportion of footage in parts one and two shows troublesome interactions between protestors and law enforcement. The non-violent Water Protectors are tenacious as they stand together in solidarity and attempt to protect sacred burial grounds by blocking access and impeding construction with their bodies. They stoically face law enforcement’s crowd controlling tactics, arguably brutal and unnecessary given the non-violent nature of the protest. They are pelted with rubber bullets, sometimes at close range, and are hosed with water cannons in freezing weather. They are doused with mace and tear gas, dogs are unleashed upon them, and barbed wire is strung in their path.

The film reveals its central thesis at the beginning of part three, after concisely explaining the legal history and primary points of disagreement (U.S. Supreme Court decisions, violation of treaties, and “perpetual and continuous theft of natural resources”), Standing Rock is “just one of the many corporate attacks currently occurring in every indigenous community globally.” Cornel West, well-known African American academic and activist, delivers a cogent clarion call, warning that the movement has been labeled as domestic terror, and thus, domestic resources are being used to repress activists on behalf of a corporate entity. He views this as the repression of sovereign nations. Dewey’s part three is a primer on police-protester relations and constitutional rights. He asks critical questions: What constitutes brutality? Who and what are being protected? He documents the movement’s efforts to connect with members of local law enforcement and discusses the need to educate non-natives with regard to cultural protocol. The film ends with referrals to informative websites and an unabashed, heartfelt appeal for viewers to join the Water Protectors and to divest from corporate banks who fund the oil and gas pipeline industry.

If you are looking for a film that comprehensively shows both sides of this issue, this is not your film; it devotes little time to explication of opposing viewpoints. But the film’s strengths are numerous: it gives space for American Indian voices, provides an exemplar of the ethos of non-violent resistance, and demonstrates a spiritually-infused worldview that values connectedness. The film is important on three levels: as an archive of the events; as documentation of the zeitgeist and fervid motivations behind a non-violent social movement; and as a pathfinder showing possible ways to bridge the chasm, to end the apartheid that divides us as people. Non-violently connecting is the first step. The lyrics of the song Love Letters to God (sung by Nahko and Medicine for the People) poignantly play at the film’s end and pique concluding questions about non-violence: “Provoke us to fight / So we burn a little sage and write poetry / Wiser than the enemy will ever be / The minority / And authority / Are you here to protect or arrest me?” Though the gulf between the corporate, pro-extractive industry values and the pro-environmental, indigenous views seems wide as the Missouri, the filmmakers seed hope of relationship with Nahko’s song lyrics: “So many parts to a heavy heart / If there’s no beginning, then where would you start? / Start, start, where would you start?” Educators and students can start by viewing Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock, and begin to critically examine the intransigence of each side. The film will spark discussion of indigenous rights, and whether law enforcement is skewed toward protection of corporate interests to the detriment of said rights. The film is highly recommended to support curriculum in the following fields: law enforcement; human rights; environmental, peace, policy, and ethnic/Native American studies; also, broader social sciences curriculum such as anthropology and sociology would be well-served, as would law school students studying constitutional law.