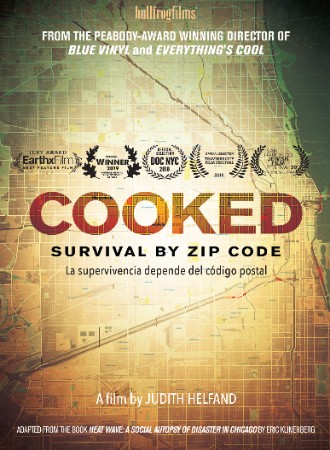

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code 2019

Distributed by Bullfrog Films, PO Box 149, Oley, PA 19547; 800-543-FROG (3764)

Produced by Judith Helfand and Fennell Doremus

Directed by Judith Helfand

Streaming, 121 mins

College - General Adult

African American; Disasters; Urban Studies

Date Entered: 04/16/2020

Reviewed by Timothy W. Kneeland, History and Political Science Department, Nazareth College of Rochester, Rochester, NYAs disaster professionals know, there is no such thing as a natural disaster. Disasters occur when public policies place people in situations that can cause physical harm and death. It is this logic that informs Cooked: Survival by Zipcode. The film opens with a look at the 1995 Chicago Heatwave that is estimated to have killed 739 people. Estimates are necessary because city officials do not have an exact account of the dead. This heatwave fell, as most disasters do, disproportionately on the most vulnerable populations. In Chicago, the elderly, impoverished, and African American communities were the hardest hits and received scant attention during the July heatwave. Filmmaker Judith Helfand was inspired to make this documentary after reading Eric Klinenberg’s book, Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, which studied the heatwave and presented a careful analysis of the people and the neighborhoods most affected by it. The disaster was not the heatwave but the failure of officials to address the needs of communities who were incapable of fending off the oppressive heat by relocating to cooling spaces such as stores, movie theaters, or malls. These areas also lack parks and trees, which would have absorbed some of the heat through natural processes. Finally, these individuals had no means to purchase air conditioning, and many were so fearful of being robbed or assaulted that they nailed their windows shut and exacerbated the heat. Helfand concludes that it was official neglect and not the weather that killed these people, which leads her on a quest to question the entire idea of natural disaster. Her central message is that U.S. policymakers must expand the definition of disaster and crisis management from centering on natural hazards such as earthquakes, tornadoes, or heatwaves to the ever-present crisis of our cities which contain vulnerable populations on whom natural hazards, such as the '95 heatwave or Hurricane Katrina in 2005, fall most heavily.

The film is strongest in the first half of the documentary when examining the heatwave. Helfand does an excellent job of coupling archival footage of then-Mayor Daley and Medical Examiner Dr. Edmund Donoghue with interviews with city and community members. The interviews with epidemiologist Steve Whitman, retired Cook County Chief Medical Officer Linda Rae Murray, author Eric Kleinenberg, disaster expert Michelle Landis Dauber, and community members from the afflicted neighborhoods are very affecting. The film is on less firm ground when Helfand takes to the road to examine current practices in disaster training and preparation in places outside of Chicago. In this segment, Helfand tries to get subjects to re-examine their premises about disasters. The underlying assumption of Helfand's question is significant and worthy of serious debate. However, this part of the film falls short of its goal. The people she questions are technical experts in disaster preparation and not elected officials equipped to re-examine the urban crisis revealed during the Chicago heatwave.

At 121 minutes, the film would be challenging to fit into one viewing in a traditional college or high school classroom but a 54 minute classroom version, available on DVD, could make this possible.