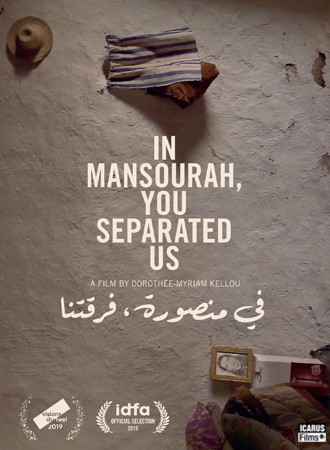

In Mansourah, You Separated Us 2019

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Mariem Hamidat, Eugenie Michel-Villette, and Sara Stockman

Directed by Dorothee Myriam Kellou

Streaming, 71 mins

College - General Adult

Algeria; History; Post Colonialism

Date Entered: 06/03/2020

Reviewed by Michael Pasqualoni, Librarian for Public Communications, Syracuse University Libraries“France did many things. It did not settle for little. Oh daughter! France did many things to us.” A recitation we hear within In Mansourah, You Separated Us, drawn from a fuller statement about the effects of international conflict on the lives of average people. The film takes us along with Malek Kellou on a homecoming journey to the Kabylia region of Algeria. For the first time in close to half a century, Malek revisits locations where as a child he lived in one of several thousand French resettlement camps established during Algeria’s war for independence. Documented by his daughter, Dorothee, the two introduce us to textures and testimony of his contemporaries as they address the legacy of an often bloody struggle. We encounter the lasting images and wounds from that battle with a colonial power that interrupted youth and continue to shape adulthoods.

Daughter Dorothee, a freelance journalist in France who has done academic study of Arab affairs and international relations, presents not the scholarly perspective on colonialism nor a comprehensive timeline or assessment of leadership decisions. Instead, In Mansourah works best as a set of oral histories. Its witnesses reflect on the sweep of events that sometimes overpower individual lives during wartime. Parents and children suddenly separated, compromised living conditions, and portraits of determined resistance. This is the narrative of the people not the powerful.

The film also is a tale of generational bonds and a singular tribute to a father. During one especially effective moment, we gather with Malek, Dorothee, and several persons whose travails have been shared, as multiple generations watch a video projection directed onto a stone façade. This film within the film depicts children and adults from the period of the war for independence. In the black and white archival footage are the young boys that could now be these same older men gazing back into their pasts. Young Algerian children of today look ahead at kids like them who are their forbears.

As much as 50% of the rural populations were subjected to forced relocation as Algeria fought for independence, but even more than a factual retelling, this documentary is a lyrical lament. We learn about interactions between villagers and esteemed military leaders (e.g., Amirouche Ait Hamouda), and of bombings that see use of Napalm by French forces. “75 men met eternal sleep,” goes one recollection. Testimonies, at times come with the pause one associates with processing trauma, and they share tales of sudden relocations without advance notice, curfews and barbed wire enclosures. They also speak of contending with threats from above (e.g., students of the period know this is the conflict helicopters were first used in battle for purposes of ground attack). We see the resettlement tents and modest thatched roof stone residences, both as they were decades ago and sometimes as rubble in their present-day condition. These are places into which, as witness Aldja recounts, multiple families were sometimes crammed seven families into one home.

Viewers unfamiliar with colonization and conflict tied to Algeria and France may want to review encyclopedic historical summaries prior to viewing In Mansourah’s more personal reflections, which explore questions of meaning and justice. The film itself directly asks of its witnesses and us, why don’t young people in both nations know this history? In some moments, an established sense of broader geographic place within the film can feel ambiguous. An unclear mapping of exactly where we are. However, as a visual memoir with a contemplative editing aesthetic, this matches both the claustrophobia of a life under occupation by a foreign power, and a rather smart perspective as well on how any child dealing with the war for independence, as it happened, probably would perceive the violent displacement recounted within the film. Not all questions here lead to easy answers. In the face of millions forced to leave their homes, a daughter asks her father, “Why didn’t the people rebel?”

Awards:

Brouillion d'un reve Award at SCAM (Societe' Civile des Auteurs Multimedia); First Prize Historical Film Projects-Rendez-Vous de l'histoire de Blois; First Prize Rough Cut Workshop - Cairo International Women's Film Festival