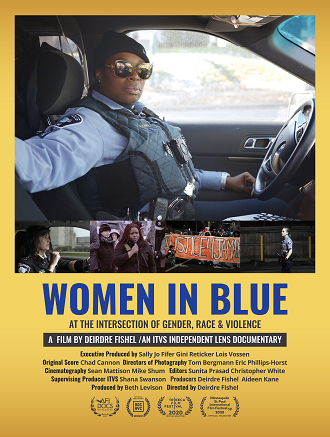

Women in Blue 2020

Distributed by Good Docs

Produced by Deirdre Fishel, Aideen Kane, and Beth Levison

Directed by Deirdre Fishel

Streaming, 88 mins

College - General Adult

African Americans; Criminal Justice; Law Enforcement; Race Relations

Date Entered: 03/11/2021

Reviewed by Timothy Hackman, University of MarylandContent Warning: This program contains images of police violence, and of conflicts between police and citizens, that may be disturbing to some viewers, as well as adult language. While it stops short of showing footage of actual killings, it does include the body camera footage leading up to such events, and audio of at least one police-involved shooting.

Women in Blue began filming in 2017 and finished in 2020, soon after Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, an unarmed Black man accused of passing a counterfeit $20 bill at a convenience store. Officer Chauvin put his knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck for over eight minutes while the 46-year-old called for help, called for his mother, lost consciousness, and eventually died. The timing is an incredible coincidence for the filmmakers, but we can clearly see the roots of that brutal incident in the culture of the city’s police department throughout Dierdre Fishel’s documentary. Women in Blue follows several female police officers, Black and White, as they navigate the complexities of a police force that is historically and predominantly White and male, in a city with some of the worst racial disparities in the country. The film presents a layered and nuanced look at a thorny situation that has, unfortunately, been overly simplified to a debate over Black lives vs. “Blue” lives. The result is a film that, while well-made, is unlikely to sway anyone on either side of that debate, although it may suggest some ways to move forward to a more honest and productive discussion.

The film opens with Chief Janeé Harteau taking the reins of the Minneapolis Police Department, the first woman to ever hold that position. Chief Harteau seems to be a thoughtful and dedicated public servant, who states her “goal as police chief was creating change from within,” even as she acknowledges that “law enforcement has long been a culture of disrespect and discrimination, most often as acts of violence against people of color.” Her introduction is intercut with photos of the ranks of Minneapolis police officers, all white and male, to show the environment she inherited. We quickly shift scenes to an April 2017 swearing-in ceremony for newly promoted sergeants, in which one woman after another comes forward to claim their new ranks. Chief Harteau focused on promoting women, who are statistically less likely to use force, into leadership positions all across the department as part of broader efforts to change the culture that also included promoting people of color and department participation in federal training initiatives.

In addition to Chief Harteau, the film follows four female police officers -- Alice White (a Black officer with a teenage daughter), Erin Grabosky (a White rookie officer partnered with another rookie officer who is male and Black), Melissa Chiodo (a White commander of the Special Crimes unit, focusing on domestic violence and sex trafficking), and Catherine “CJ” Johnson (a White Inspector and head of Minneapolis’s 3rd Precinct.) The cameras follow these women as they go about their daily duties -- meeting with leadership and fellow officers, going on patrol, responding to calls, attending community meetings, and more -- as well as talking with their families about the work that they do. They all seem to respect Chief Harteau and appreciate the approach she has taken emphasizing women in leadership positions, even as they recognize the inherent difficulties of changing something as complex and ingrained as the culture of an entire police department. The film does a good job of showing how the presence of women in such roles can make a difference (or not, in the case of Officer Grabosky) in how police officers respond to calls and deal with the citizens they are supposed to protect and serve.

The turning point comes when a high-profile shooting by a rookie officer leads Mayor Betsy Hodges to call for Chief Harteau’s resignation, and when the Mayor subsequently appoints Assistant Chief Medaria “Rondo” Arradondo, who himself had been promoted four times by Harteau, as the new chief. Although Arradondo is met with enthusiasm from the community as Minneapolis’s first Black police chief, the four women officers are concerned that his failure to select a single woman for his new executive team -- Inspector Johnson, in particular, was in position to be promoted, but was passed over by two lower-ranking male officers -- is a signal that Chief Harteau’s focus on cultural change is about to be abandoned. And indeed, the events captured by the film seem to bear that out. At a meeting with officers, new Deputy Chief Art Knight tells the group, “F*** Rodney King… He deserved to get his ass whooped,” and talks up the “good old days” of rampant police brutality: “You know what, I don't even want to lie, it was fun back in the day. Some of the stuff we used to get away with, but it wasn't right because I've seen a lot of good cops lose their jobs, pensions, careers over knuckleheads.” Obviously, a member of the leadership team who expresses concern only for the officers’ jobs, careers, and pensions, and not for what is right or wrong, sets a poor example for the rank and file. Similarly, when questioned about his failure to appoint any women, Chief Arradondo echoes the same tired arguments that those engaged in equity and diversity work have heard for decades, that he just chose the “right” person for the job: “I had to make sure that I was very considerate and intentional in making sure I had the right people at the right time in leadership.” Later in the film, when Commander Chiodo meets with him and brings up the role of women in department leadership, including why more women are not applying for promotion, he responds by volunteering her to do the work to investigate and rectify it.

In the wake of another shooting, this time of Thurman Blevins, a 31 year-old Black man who was carrying a gun, but who was also running away from police at the time he was killed, protests and discussions begin anew around the role of police in the community, accountability, and structural racism. A mayoral debate captured by the film sums up the varying approaches well -- one candidate (a Black woman) leans into “defund and divest;” the incumbent (a White woman) discusses concrete plans for funding additional community initiatives and partnerships; and a White man (and eventual winner) wants even more funding for police. Police Union President Bob Kroll, who would later gain notoriety in the wake of George Floyd’s murder for calling Black Lives Matter “a terrorist movement” and Floyd a “violent criminal,” is interviewed to express the predictable opinion that “we need to keep politics out of policing. If the politicians stay out of their way, policing will be great in Minneapolis again.” (He also praises the actions of the officer who shot and killed Thurman Blevins as “nothing short of heroic activity.”) The presence of figures such as Kroll and Knight hint at the forces aligned against meaningful change within policing and help make the case for new approaches such as “defund and divest.”

Overall, Women in Blue makes for compelling viewing for the access it offers to women both on the front lines and in leadership positions in the police department of a major American city, and for its portrait of the turmoil within the Minneapolis Police Department in the years immediately before the murder of Mr. Floyd. The women it profiles are complex, as all humans are, and are allowed to express their conflicting opinions on the job that they do with little interference from the filmmakers. Officer (later, Sergeant) White, for example, admits that she often tells people only that she “works for the city,” and expresses frustration that the department of 850 officers has just six Black women and “NO Black female sergeants on the street right now.” But she is also slightly defensive about criticisms of her profession, expressing the opinion that “It’s not just law enforcement that needs to change,” though it is unclear exactly what she means by this, and the film would have benefited from some additional prodding by the filmmakers here. The scenes between White and her teenage daughter Dara are especially illuminating, as the two discuss what Dara’s peers think of her mom’s job, and we see mother and daughter’s reactions to the video of George Floyd’s murder. Nekima Levy-Pounds, who campaigned unsuccessfully against Hodges and others for the job of mayor, offers a fitting summary of Women in Blue: “It shouldn’t be a zero sum game. We shouldn’t have to choose between no police and extremely violent police. And so now with the world watching, my hope is that this is a wake-up call, that this is a reckoning. We need a paradigm shift.” Hopefully, the types of conversations started by this film could be the beginning of that paradigm shift.

Note: This program was previously broadcast on the PBS series, Independent Lens. It is available for 14-day streaming (hosted by Good Docs,) perpetual streaming (locally hosted,) or DVD. A transcript of the program is included as a Word document, which is incredibly helpful for accessibility.

Awards:

Audience Documentary Award, Filmocracy

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.