Donbass 2018

Distributed by Film Movement

Produced by Heino Deckert

Directed by Sergei Loznitsa

Streaming, 122 mins

College - General Adult

Russia-Ukraine War; Russian/Slavic Studies

Date Entered: 09/14/2022

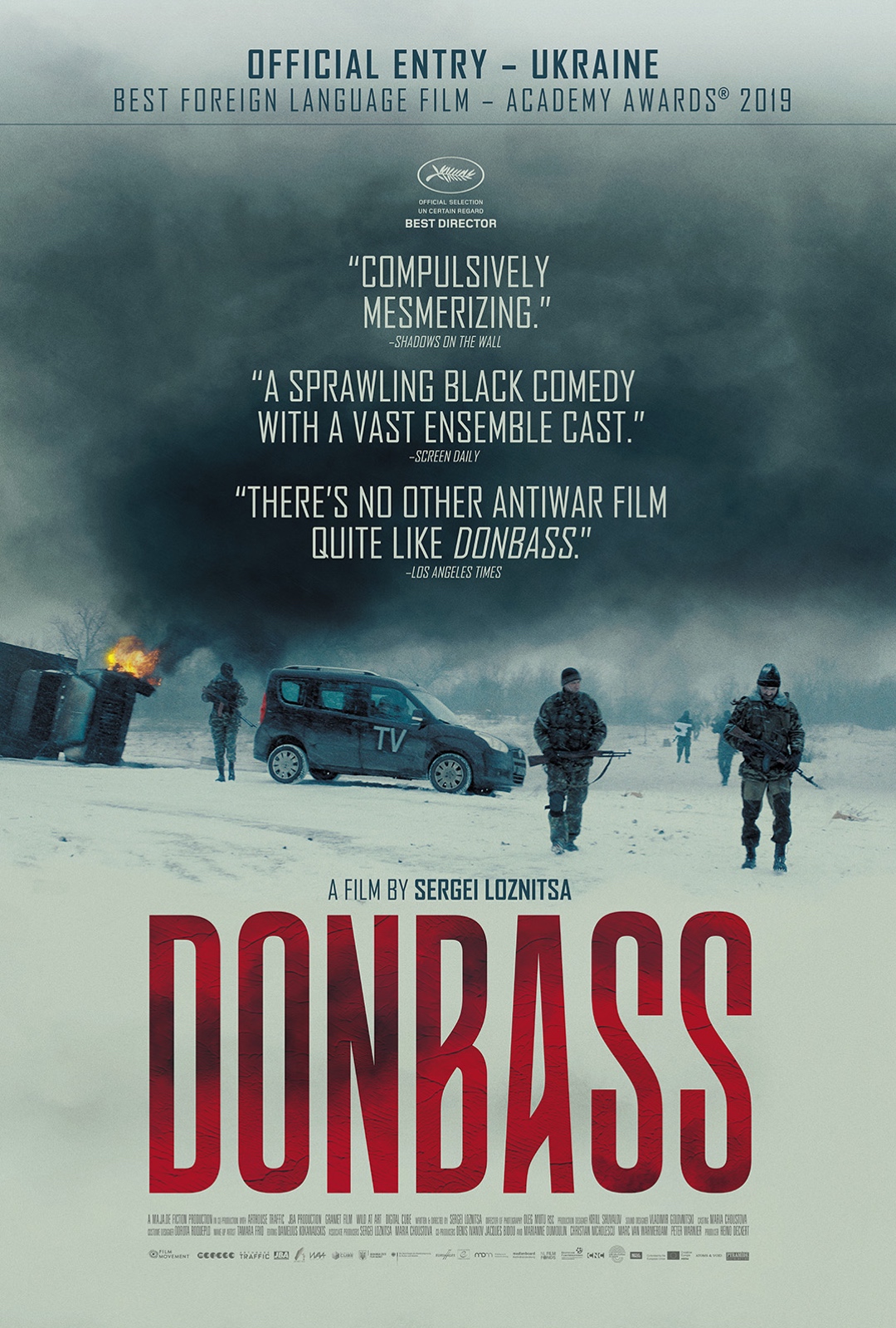

Reviewed by Andy Horbal, Cornell University LibraryDonbass might be one of the most important films of the 21st century, but it nearly didn’t make it to more than a handful of American screens. Shot in 2018, it dramatizes events which took place in the early days of the Russian-Ukraine War that started in 2014. Following an auspicious debut at Cannes, where Sergei Loznitsa won the Best Director award in the Un Certain Regard section, it went on to additional success on the festival circuit and was voted the second-best undistributed film of 2018 by participants in IndieWire’s annual Critics Poll. In 2019 Ukraine submitted it for consideration for that year’s Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, but it was not nominated and disappeared off most cinephiles' radars shortly afterward.

The story might have ended here, but then Russia invaded Ukraine in February, 2022. With the world looking for answers about what was happening and how it got started, Donbass was finally released theatrically in the United States the following April and is now being brought out on Blu-Ray/DVD by Film Movement. The movie is a harrowing depiction of life during wartime constructed out of about a dozen vignettes set in various locations across Eastern Ukraine. Viewers who don’t speak Russian or Ukrainian or aren’t well-versed in the politics and culture of the region may occasionally feel disoriented, but the titles which give it structure are effective at informing even the uninitiated where the action is taking place and which side all the characters are on: when we’re in “Occupied territory in Eastern Ukraine,” for instance, it’s obvious that government officials and soldiers must be associated with the separatist movement.

Although Donbass doesn’t have a single narrative through-line, the episodes that comprise it flow into and echo one another as characters and news travels back and forth across Ukraine. They also share common themes, such as the manipulation of “facts” by people in positions of authority. The film is bookended by scenes beginning with actors being made up to play roles as eyewitnesses to attacks on civilians for a television news broadcast which appears in the background elsewhere in the movie, for instance. Another segment features a government official explaining to the staff of a maternity hospital that they weren’t ever really under-resourced by showing them a room full of essential supplies which he claims were being hoarded by their corrupt former head physician–who we subsequently find out is sitting in the next room with his mistress waiting for the same official to smuggle him out of the country.

There’s no doubt that the filmmakers’ sympathies lie more with the Ukrainian national forces than those of “Novorossiya,” but few specific characters are clearly coded as being good or bad. Rather, the emphasis is on what Loznitsa has described in interviews as the dehumanizing effects of war. His main argument is that it creates an environment in which everyone looks out for their own interests first and foremost with results ranging from absurd to tragic. The best example of the former end of the spectrum is a story about a man who arrives at a regional police headquarters in occupied territory to retrieve his stolen car, which was recovered by the military. The soldiers who are using it when he gets there send him inside to “sort out some formalities.” He realizes too late that they never had any intention of returning the car, but rather summoned him in order to get his signature on paperwork officially transferring ownership of it to them. The scene ends with a surreal 90 second-long shot of a room full of well-dressed men under armed guard pacing back and forth as they call everyone they can think of on their cell phones in an effort to scrounge up bribe money to secure their freedom.

This is one kind of individual’s vision of hell. A perhaps more universal nightmare is brought to life in the very next scene. Two soldiers leave the room full of men talking on their phones. When we next see them, they’re escorting a third man in military fatigues who has a Ukrainian flag tied around his neck and a sign taped to his stomach which reads “EXTERMINATION SQUAD VOLUNTEER.” The occupation troops tie him to a pole because they “want people to look into his eyes.” A crowd of rowdy young men gathers around him and begins to pose for cellphone pictures and videos of them blowing smoke in his face. Soon others arrive, including an old woman who first attacks him with her cane, then smashes a tomato in his face. Within seconds they have turned into a violent mob, hitting and kicking the prisoner of war even as he is (finally) led away by his captors.

The cellphone footage reappears in the next vignette when some of the youths show up at a bizarre, (Novorossyian) state-sponsored wedding as guests and proudly display it to the groom, who says “cool!” Cameras and screens feature prominently in Donbass in other ways as well, including sometimes in the form of point of view shots. Interestingly, such scenes always end with the camera appearing on screen, further reinforcing the idea that one of the distinguishing features of modern warfare is that the lines between experiencing and documenting it are as permeable as the border checkpoints which appear throughout the film.

Donbass is about incidents which took place in Ukraine almost a decade ago, but viewers turning to it to learn more about what’s occurring there now will surely emerge with a better understanding of the current conflict. It’s also a timeless reminder of cinema’s enduring but ever more frequently unrealized power to make distant times and places real for audiences. One can’t help but wonder what might be different now had more people seen this film in 2019–would they have taken the threat Russia posed to Ukraine more seriously, and if so, could they have influenced their governments to do something about it? And, regardless, what other movies should we be placing closer attention to now? In any event, it’s hard to imagine a library collection anywhere that wouldn’t benefit from the addition of this essential film.

Awards:Un Certain Regard, Directing Prize, Cannes Film Festival; Best Film, Ukrainian Film Academy Awards; Best Director, Ukrainian Film Academy Awards; Best Screenplay, Ukrainian Film Academy Awards

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.