Merle Oberon: The ‘Trouble’ with Merle 2003

Distributed by Chip Taylor Communications, 2 East View Drive, Derry, NH 03038-4812; 800-876-CHIP (2447)

Produced by Film Australia and David Noakes

Directed by Marée Delofski

VHS, color, 55 min.

Adult

Communication, Biography, Film Studies

Date Entered: 12/10/2003

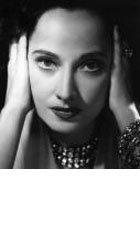

Reviewed by Michelle L. Zafron, Health Sciences Library, University at Buffalo, State University of New YorkSay the name Merle Oberon today and a few people may remember her as Cathy in Wuthering Heights. In her day though, she was a bonafide movie star. Merle Oberon: The ‘Trouble’ with Merle is not, however, about Oberon’s career and life, but rather deals with the mystery behind her origins. The “trouble” of the title is the multiple versions of Oberon’s origins. In her documentary, Marée Delofski attempts to find the truth hidden in the several extant persuasive fictions.

The “official” story that studio publicists created and promulgated has Oberon born in far-flung Tasmania, and raised in India by upper-class godparents. Oberon clung to this fiction for the rest of her life, even visiting Tasmania for what was termed a “welcome-home” tour in 1978. The truth came out in a posthumous biography: Oberon was Anglo-Indian in an era where a mixed-raced background would have been enough to keep her from starring in British and American films. Tasmania was chosen because it was so remote, respectably British, and yet still exotic.

There’s still another version, one whose proponents cling to with the same tenacity as Oberon did to the Hollywood concoction of lies. Many Tasmanians, a people who have always been fiercely proud to claim her as their own, are fiercely convinced that Oberon was the illegitimate daughter of a Chinese domestic and a Tasmanian hotelier. Intrigued by this idea and intent on deciphering the truth, Delofski follows the anecdotal chain of evidence on a journey that takes her into dozens of homes and across several continents.

Buried deep within this gossipy, sometimes bizarre documentary is a gem of an idea that might have made for a really good piece. Why, in fact, are so many Tasmanians so determined to believe Oberon was Tasmanian? How did such an extraordinary alternative version evolve? Why did Oberon make a “return” journey to Tasmania? At what point do truth, myth, and memory meet? These are all questions that Delofski proposes from time to time, promises to address, but never quite answers. One has the sense that either the nebulous nature of Oberon’s origin stories overwhelmed her or the answers just got lost in the editing.

The production values are good overall. Delofski intersperses segments of the documentary with clips of Oberon’s films, which function as narrative commentary in a quirky but effective enough fashion. As biography or film studies go, this is not a useful source, but there is enough of interest to warrant purchase in academic collections that support Communications.

Awards:

- NSW Premier’s Audio/Visual History Prize, 2003

- NSW Premier’s Script Writing Award, Finalist, 2003