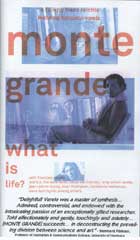

monte grande-what is life? 2004

Distributed by First Run/Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by T&C Film, Zürich

Directed by Franz Reichle

VHS, color, 80 min.

College - Adult

Philosophy, Science, Psychology, Religious Studies, Health Sciences, Death and Dying

Date Entered: 08/09/2005

Reviewed by Charles J. Greenberg, Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale UniversityChilean neuroscientist Francisco Varela (1946-2001), possessing an extraordinary gift of emotional intelligence, academic prowess, and international peer recognition by the age of 25, experienced abrupt personal and professional disorientation in the chaos and violence that shook his Chilean homeland during the 1973 military coup. Searching for a personal philosophy of life that would complement his emerging thoughts and theories of perception and cognition, Varela was drawn to Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and practice. Adopting the unity of mind and body and subjective-objective undivided consciousness as a central tenet of perception, Varela experienced not only blossoming popularity among the 1980’s new age cognitive research audience, but also a core set of spiritual values and meditative practices that inspired others during his extended fight with cancer.

Franz Reichle, director of monte grande - what is life?, faced a considerable editorial challenge in attempting to present an objective account of Varela’s life for the uninitiated, even as Varela himself posits his conviction that there is no objective reality, only integrated subjective encounter with the world, what Varela terms “our own dance together.” The documentary contains touchstones of Varela’s life, such as childhood film clips and images, excerpts of interviews with each of Varela’s three spouses and children, and a sampling of impressions that range from luminaries such as the Dalai Lama and computer scientist Heinz von Foerster to academic acquaintances such as Harvard Professor Anne Harrington. Director Reichle presents a non-linear film sequence that intersperses the rural environment and culture of Monte Grande at the base of the Chilean Andes mountains with Varela’s admirers and families. Varela himself lecturing in different venues or musing in contemplative solitude near the end of his life form the majority of the presentation.

The friends and family that appear during the film provide narration. A placid and contemplative original soundtrack features soft Tibetan chanting. Some previously recordings of Varela are presented with minimal re-editing. In contrast to the unpredictable sequence for portraying Varela the person, one aspect Monte Grande culture is given a linear and unifying role to represent an unchanging reality. A home baker constructs empanadas, first the dough and then the filling, in several unhurried and methodical steps interspersed throughout the film. In the shadow of the Andes, a daily ritual transforms natural bounty into a kind of subjective unchanging truth. Made without automation, no two empanadas will ever be identical, nor taste identically in any subjective experience. The baking sequences also provide visual refreshment for viewers that grow weary of philosophic declarations. Most of the speakers use English language in their presentations, and English subtitles accompany some segments, even the decent English of the Dalai Lama. The visual sequence offered at the beginning, prior to the Valera’s first appearance, could be interpreted in a variety of ways, but might be a bit disconcerting for contemporary younger audiences with impatient tendencies.

College and adult audiences could benefit from this compact interdisciplinary introduction to one internationally respected theoretician of perception that rejected the mainstream theoretical information-processing model of cognition. One viewing may not provide enough opportunity for students to personally engage the complexity of Valera’s integration of cognition with Buddhist philosophy and practice, so I would recommend that if the video is used in a classroom setting, it should subsequently be put on reserve for individual review. I personally benefited from watching the video more than once. No, I was not writing down the empanada recipe.

Recommended.