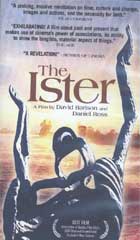

The Ister 2004

Distributed by First Run/Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by David Barison and Daniel Ross

Directed by David Barison and Daniel Ross

VHS, color, 189 min.

Sr. High - Adult

Philosophy, History, Technology, Ecology, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Date Entered: 08/26/2005

Reviewed by Cheryl Danieri-RatcliffeThere are a whole series of reasons why this film should not succeed. First, it was made by two young Australian intellectuals, neither of whom had any previous experience in filmmaking, who arrived in Europe to begin filming with no clear idea of how to shoot it and with no outside funding. They bought a hand-held Sony mini-DV camera and a twenty-year-old bread van and set out to capture images along the nearly two thousand mile course of the Danube river and to carry out interviews in which they gave what should have been the dangerous privilege of allowing three French university professors and a German filmmaker generous time to expound upon what seem to be prepared answers to questions they were asked. Bernard Stiegler, a philosopher, is given the largest share of time talking at length in French and adding irritating brief sentences in English to the accompaniment of off-screen noises and interruptions.

Second, it addresses complex issues in philosophy and thus poses the dilemma of how abstract ideas can be presented in images as well as in sound in a film documentary. Worse, it grapples with the work and legacy of Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), a philosopher whose thinking was not only complex – he himself once appropriately wrote that “making itself intelligible is suicide for philosophy” – but remains highly controversial. His influence can be traced in existentialism, deconstructionism, and hermeneutics but even there this influence remains ambiguous: he himself contested the existentialist Sartre’s interpretation and, although they have been greatly influenced by his work, each of the three philosophers interviewed in the film also contest facets of his thinking. In any case, Heidegger’s work is muddied by his links to National-Socialism – he joined the party in 1933 and, following Germany’s defeat in 1945 never came to condemn the Third Reich in general and the Holocaust in particular. How could such an outstanding twentieth-century philosopher give support to the century’s most abhorrent regime? The answer to this question remains hotly debated.

Despite all these seemingly insurmountable difficulties, this brave, original, and well-crafted film has met with critical acclaim and considerable success with audiences at film festivals, though, inevitably, it has not found a place on the commercial circuit. Why is this so? It succeeds against the odds because Barison and Ross, its directors, began with a shared interest in philosophy and an admiration for Heidegger – Ross was already writing a doctoral thesis on him – and a willingness to spend five years on a labour of love. It works for another reason: Heidegger is text and pretext. The film does not attempt an exposition of the German thinker’s ideas, some of which changed over time, but discusses issues – modernity, technology and culture, memory and forgetting, Being and anxiety, ecology and politics – that Heidegger raised in his work as a whole and which, of course, remain critical issues in our world. Their discussion also benefits from their good fortune in securing the collaboration of their four principal interviewees – three of whom, Stiegler, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, are leading, if critical, exponents of Heidegger’s philosophy and prove better able to explain ideas to a general public than we have a right to expect from French academics. Lacoue-Labarthe also addresses the equation between high-tech agriculture, Nazi gas chambers and the Hydrogen bomb that Heidegger infamously and ambiguously made in 1949. In the film’s final sequences, the fourth interviewee, the German filmmaker Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, best known for Hitler: A Film from Germany (1977), makes challenging comments on his country’s past and present. Yet another reason why The Ister works is that Barison and Ross chose to anchor their film on Heidegger’s reflections in lectures he gave in 1942 on an unfinished poem of the same name the German Friedrich Hölderlin wrote in the first decade of the previous century (lectures, incidentally, that were only published in 1984 and in American translation in 1996). The Ister is the Greco-Roman name for the Danube and the filmmakers use their shots of the river to illustrate and highlight issues raised by their discussants. By judicious editing, they do so in sometimes humorous and usually stimulating ways and construct a metaphysical journey from where the river flows in the Black Sea in Romania back to its source in the Black forest in southern Germany, near Heidegger’s birthplace. By felicitous filming they capture critical moments and places along the Danube that reflect triumphs and tragedies in past and present: May Day in the steel city that used to be called “Stalintown” in Hungary; a site of NATO bombing in Yugoslavia, the arrival of the Peace Train at Vukova in Croatia that commemorates one recent conflict in the Balkans; the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria; the Danube festival in Regensburg… Despite the brilliant editing and clever filming, The Ister grapples with difficult if fundamental issues, especially about man and machine, memory and identity, and the pace is necessarily slow. Even though there is an intermission, it still lasts over three hours and is not easy to watch. For its daring and challenging nature, though, it is well worth the effort and no-one comes out of the experience without having been made to think. The Ister is, as Lévi-Strauss said in another context, “good to think.”