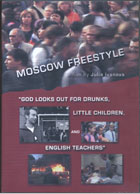

Moscow Freestyle 2006

Distributed by Interfilm Productions Inc.,, 304-1515 West Hastings St., Vancouver, BC V6G 3G6, Canada; 604-638-8920

Produced by Julia Ivanova

Directed by Julia Ivanova

DVD, color, 51 min.

College - Adult

European Studies, Post-Soviet Russia, Multicultural Studies

Date Entered: 08/20/2009

Reviewed by Andrew Jenks, California State University, Long BeachIn search of romance and adventure, young Westerners from Canada, the United States, and Great Britain packed up their suitcases in the early part of the 21st century and signed on to teach English in Russia. It has long been a common rite of passage for many graduates of college with liberal arts degrees to take a sojourn in exotic foreign locales. Instead of big bucks they hoped to receive their salary in big adventures. The experience would satisfy a hunger for adventure and build up a lifetime’s worth of stories to impress friends back home. This film tells the story of a group of adventure seekers—English-language teachers in post-communist Moscow.

The action takes place in Moscow in the summer of 2004. For Muscovites, the summer of 2004 was the summer of terror: bombings in metro stations, shootouts with Chechens, the dramatic and bloody taking of school children in Southern Russia. Recounted over and over again in the Russian media, the terrorist attacks (real but also imagined) raised tensions in Moscow during that fateful summer to a fever pitch. The documentary injects snippets of newscasts from that summer to convey the climate of paranoia and fear. Cops harassed foreigners—especially those who seemed “dark” and spoke Russian with an accent—a sign, perhaps, of belonging to shadowy Chechen terrorist organization. The cameras followed the young teachers to their classrooms, to their dingy apartments, to the streets of Moscow for beers, where they engaged in often hostile conversations with a variety of Russians. Many Russians with whom they conversed dropped casual racist comments about blacks, Jews, and Chechens—racist beliefs that many Americans might share but for reasons of political correctness would probably dare not utter. Perhaps one of the biggest shocks for the young teachers of English is the ease with which Russians slip into ethnic and racial stereotypes to categorize people and understand the world around them. Russia, they discover, is a politically incorrect culture—a quality of Russian public life that the teachers find both fascinating and shocking. The main protagonists of this documentary, young teachers of English, attempt to find a sense of purpose and belonging in this atmosphere of fear and terror. The three main subjects of the film, who have been working in Moscow for a number of years, have made a concerted effort to adapt to Russian culture, learning the language and mastering the nuances of bribe-giving and finagling registrations from corrupt police. They experience the anarchic sense of freedom that pervades post-Soviet Russia, a land where “nyet” does not mean no but is the beginning of a bargaining process, usually involving bribes. Where there are no clear rules anything is possible, provided you have money and power.

Much of the documentary focuses on a young Canadian man who thrives on the intellectual challenge of thinking constantly in two languages. Much of Moscow in this film is viewed through his eyes—as he drinks and smokes to excess, as he muses over his failed attempts to pass for being a Russian. Though his Russian language skills are excellent, he admits that he can never fully assimilate. At one point, a Russian colleague mocks and belittles him for his accented Russian. It is especially humiliating, since he has clearly made such an effort to speak colloquial Russian. The insult adds to the daily humiliations of being scolded by grandmothers on the street, asked for one’s documents, and generally being made to feel like a stranger who can never understand the mysterious Russian soul. “You can’t understand Russia with the mind,” as the Russians like to say, especially to foreigners.

The young Canadian concludes at the end of the film that Russia for him is an unrequited love. He will love Russia but it will never love him back, as he discovers whenever he has to get his documents in order. Acquiring registrations is a tedious yet essential process for gaining permission as a foreigner to live and work in Moscow. Getting a registration often requires bribes—and even having a registration, which cops will invariably demand on the street, does not exclude the registrant from paying out bribes to avoid further trouble. As one Russian tells him, if he doesn’t pay a bribe during a routine check, he might get hauled to the police station and perhaps have his passport inadvertently flushed down a toilet. Then there would be real trouble.

It is curious that the subjects of this film did not see a parallel between their situation in Moscow and the situation of many illegal immigrants and semi-legal foreign workers back in their home land.

Be that as it may, there was a time when Muscovites admired and loved Westerners, especially during the late 1980s. Not so in Putin’s Russia. By 2004, the foreigners have lost their appeal. To Russians they are no longer interesting. Some Muscovites clearly despise them, but mostly they could care less about them, perhaps the greatest insult. What Russians need to know about America they seem to get from pirated videos of Hollywood films.

So, the foreigners hang out with themselves and commiserate—acknowledging, however, that life in Moscow is incomparably more interesting than the crummy little town back home from whence they came. Their sojourn seems to have become a form of masochism. Their contacts with Russians are fleeting, unsatisfying and often hostile. They experience the xenophobia that is part of the new nationalism in the era of Vladimir Putin. To be Russian a la Putin, they discover, is to express disdain for all things non Russian, especially American. One young Russian whom they encounter while drinking in a park is in school to be a cop (a militia man in Russia). He explains that pay is so low for cops that they have no choice but to demand bribes simply to live. Their discussion turns to a comparison of the Russian AK-47 and the American M-16. The young Russian mocks the M-16 as a pathetic killing instrument, wonders why “Africans” rather than “real Americans” populate sports teams in the United States, and mocks American soldiers as coddled wimps for supposedly having to “drink orange juice” every morning before roll call. He must have gotten that from some Hollywood film.

Perhaps most damning, the young male Westerners discover that Muscovite Russian girls have no interest in them since they have little money or access to privilege. The experience of being ignored and on occasion despised, clearly takes its toll. By the end of the documentary, the young teachers of English have a perpetual five-o-clock shadow, chain smoke, kvetch about their daily miseries, and drink constantly.

All in all, the film provides an excellent portrait of post-communist Moscow through the eyes of young Westerners. Nonetheless, it provides only a snapshot—and one that the director could have explained more clearly. The film provides no explanation about when the footage was shot. The backdrop for the documentary suggests that the filming took place in the summer of 2004, but the casual viewer would not be able to make this determination. More information about the terrifying summer of 2004 would have helped to explain why the foreigners were greeted with such suspicion and disdain—much as foreigners in the United States after 9/11, and even different looking U.S. citizens, experienced various humiliations at the hands of authorities. Second, some viewers may come away with the impression that Moscow represents Russia, which would be like saying New York City after 9/11 accurately represented the life and spirit of the United States. Moscow, like any large cosmopolitan city, is a hostile place, full of ambitious and unscrupulous wealth seekers. The pace of life is frantic. Danger and opportunity lurk everywhere. It is challenging to make friends, as in any big city. One wonders how teachers of English would fare deep in the Russian provinces. Steering the focus away from Moscow might have produced a very different portrait of the new Russia—a more balanced and sympathetic one, perhaps. Finally, conspicuously absent in this documentary is the perspective of Russians, especially those being taught by the Westerners in the documentary. Never once are they asked what they think of their teachers and how they view Moscow or Russian life under Putin. The producer channels everything through the eyes of the young English teachers. The documentary thus limits itself to a view of Russia from the outside looking in and ultimately fails to gain a glimpse of post-Soviet Russia from the inside looking out. But that would be another documentary.