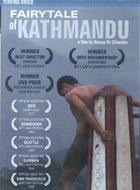

Fairytale of Kathmandu 2007

Distributed by Cinema Guild, 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800, New York, NY 10001; 212-685-6242

Produced by David Rane

Directed by Neasa Ni Chianain

DVD, color, 60 min.

Sr. High - Adult

Asian Studies, Criminal Justice, Ethics, Gay and Lesbian Studies

Date Entered: 12/17/2009

Reviewed by Dan DiLandro, E.H. Butler Library, State University of New York College at BuffaloA documentary by Neasa Ni Chianain, Fairytale of Kathmandu purports to follow the poet Cathal O’Searcaigh between his home in Ireland and his more “spiritual center” in Nepal. While beginning as a straightforward documentary of this “guru of the hills” and his philanthropic works in Kathmandu, the film increasingly investigates O’Searcaigh’s apparently unseemly and possibly illegal sexual activities with the young men of the Nepalese capital, becoming a film exposing sex tourism.

Fairytale of Kathmandu is beautifully shot and presented with subtitles of Irish Gaelic and Nepalese, and begins with the filmmaker’s relationship with the poet. They had met, she says, years before, and her impression and subsequent friendship with this author who explored his homosexuality, loneliness, lost love (and obsession over it), and rural isolation was allegedly the motivation for the documentary. Travelling to Nepal, Chianain films the poet’s interaction with the locals, triumphing his positive works and the obvious love the residents have for him. Indeed, the populace of Kathmandu seems to adore O’Searcaigh; and his young friends giggle rapturously around him.

The poet’s financial and educational support of the young men and their families is highlighted, and the film “reads” like a paean to this author and benefactor. But the film shows—or, well, never shows, but hints at—O’Searcaigh adopting a young man into his hotel room once while on a hiking trip. The filmmaker notes that she was “taken aback” at this, and generally from this point, the narrative takes on a, perhaps appropriately, suspicious turn. The hysterically amused young men whom we have met are replaced by images of sideways glances and fearful faces and a hotel manager who hints at sexual activity and allows the filmmaker to note that “people just close their eyes” and how the poet’s help “has terms and conditions.”

Speaking one on one with some other boys, they describe themselves (somewhat suddenly within the narrative flow) as “victims,” how there was inappropriate behavior, “blue films,” and so on. “He bought myself,” declares one; and it is clear that the film and the filmmaker accept these allegations.

Chianain “wanted to stay loyal…. But the things I had witnessed…” lead her to eventually confront O’Searcaigh when back in Ireland. (This confrontation, of course, introduces the filmmaker directly into the narrative, at which point we can no longer call this a documentary, really.) All of his Nepalese decorations have lost their appeal for her, hinting at the price that was paid for them. Questioning her undoubtedly fallen idol about his “use” of the young men, all O’Searcaigh angrily and worriedly responds is that “for me, that is not the truth!”

Essentially, that is the narrative of the film, but Fairytale of Kathmandu will—versus the filmmaker’s true intent, I think—undoubtedly prove avenues for a vast amount of discussion within the educational setting. Indeed, there was a good deal of debate in the Irish press and elsewhere regarding not only the poet’s alleged (and it must be, at this point, alleged; it does not seem as though O’Searcaigh has even been criminally charged with anything) behavior, but also a good deal of criticism aimed at the Chianain and her filming techniques. Some discussion is made in the film about sex tourism, and this is placed in relief on how Westerners with some money can achieve dominance over poorer people of the lesser developed world. But the film betrays some charges that it cannot answer. For example, none of the scenes of O’Searcaigh entertaining young men evidence him actively pursuing them; the boys all go to his hotel room. So, too, the film makes clear that all of these young men are above the age of consent in Nepal (but not, it seems, would all of them be in Ireland). The film does not say that O’Searcaigh is involved in pedophilia (only some type of social dominance), but this might be the reaction of some viewers, based partially on the narrative techniques. Then, some might—and have in the media—ask: What exactly is the charge against the poet? That young men approach him to trade sex (or sleeping together only or watching “blue” movies or anything) for money makes the author a “john” to their self-prostitution? Most social systems argue which one is “worse”; but implying that, as a relatively wealthy Westerner amongst poor “natives,” O’Searcaigh is forcing anyone to do anything “feels” somewhat inauthentic. What would viewers think if these young men had been young women of a similar age of consent, and how might the film’s narrative be different? Homosexuality was illegal in Nepal during the filming of this work (though the film does not necessarily note this fact), so is the filmmaker agreeing, then, with Nepal’s then-repressive and bigoted laws? This is unclear and, perhaps, somewhat unsettling. The film itself, really, might be charged with a type of “poverty porn” in its assumption that O’Searcaigh has a sort of droit de seigneur and that (willing?) young men are complete victims. To hear—twice—that 16 year old Nepalese men have “no idea what sex is” might indicate that, in its admirable desire to expose any form of sex tourism or predatory inequality, Fairytale of Kathmandu has underscored imposed differences between the West and other cultures: It seems a bit that the filmmaker has unfortunately imposed our Western views of victimhood in too binary terms; and, by not fully explaining the legality of O’Searcaigh’s actions, has undercut the exposure of a world-wide social problem that needs to be addressed. This film, though, does not quite do that.

How did O’Searcaigh go from being “as God for me” and an apparently supportive godfather, in fact, to a predatory monster? Or are there significantly diverging views here? Does he still have some, most, or overwhelming support within the Kathmandu community? Or “as word gets around,” is he excoriated by the population there? It is very difficult to note questions like these in their entirety, given the film itself.

This is all some academic speculation, of course, and not meant to prove or disprove anything at all (as, unfortunately, the film itself is generally guilty of), but it is meant to describe how Fairytale of Kathmandu will undoubtedly provide a great deal of discussion and thought regarding the nature of social dominance and the extent of personal choices. Taught in conjunction with press articles from the Irish press debate, Fairytale of Kathmandu is overall very much recommended—but not entirely for the debates, I think, the filmmaker wanted to generate. In this way, though, some of the “muddiness” of the film’s techniques might make it a better work, in spite of itself, regarding discussions on sex tourism, Western “dominance,” legalities and ethics. Thus, Fairytale of Kathmandu is recommended for collections that highlight Asian studies, criminal justice, ethics, and gay and lesbian studies.

Awards

- Best Director, Ourense International Film Festival

- Second Prize, Documenta Madrid Film Festival

- Best Documentary Barcelona International Gay and Lesbian Festival.