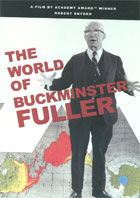

The World of Buckminster Fuller 2008

Distributed by Microcinema International/Microcinema DVD, 1636 Bush St., Suite #2, SF, CA 94109; 415-447-9750

Produced by Robert Snyder

Directed by Robert Snyder

DVD, color, 80 min.

College - Adult

Architecture, Environmental Studies, Physics, Technology, Urban Studies

Date Entered: 06/17/2010

Reviewed by Gary Handman, University of California BerkeleyAbout the time that this film was first released (1971), I was a scruffy undergraduate and Buckminister (“Bucky”) Fuller was hot stuff among some members of my corduroy-and-denim-wearing, Whole Earth Catalog-toting pals. Fuller, an endearingly odd-ball architect, engineer, and all-around visionary and futurist, is best known today as the inventor of the geodesic dome and the nutty, three-wheeled “dymaxion” car. Back in those halcyon hippie days, however, he seemed to possess startlingly unique solutions for the problems of an ecologically imperiled planet, a viable set of blueprints for the future of Spaceship Earth. The Gospel According to Bucky told us that there were more than enough resources on the planet to feed, house, and metaphysically nurture everyone, if we would just learn to harness the handful of universal principles that would allow us to logically restructure our natural and man-made environments, and to do more with less. As is the case with many visionaries, Fuller was considerably more adept at coming up with the visions than at reifying them (or even articulating them). I distinctly recall sitting through a numbingly long and shambling lecture which he gave at UCLA filled with zigzagging, nearly impenetrable gnomic riffs on physics, geometry, and cosmology. In years following, I always attributed my blurry comprehension of this talk largely to the...uh... somewhat altered state of consciousness of the majority of those of us attending. Viewing Robert Snyder’s film nearly forty years later, I’m not so sure. Snyder’s film is largely composed of segments featuring Fuller speaking to various groups (including groups of adoring, long-haired acolytes, any one of whom could have been me back then); Fuller demonstrating vector equilibrium on little Tinkertoy models; Fuller expounding his theories and concepts while sailing or relaxing at home. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of many of these sequences is their almost complete opacity to the lay viewer. Once Fuller gets rolling, it’s often as if he’s speaking in tongues—a kind of mumbled cosmic glossolalia. In short, Snyder’s documentary profile does little to immediately dispel the sense of Bucky as a brilliant crackpot with a pocketful of generally unrealizable dreams—that is, until the last few moments of the film. Toward the end of the film there’s a sequence of Fuller strolling through the Climatron at the Missouri Botanical Garden (St. Louis), a tropical rainforest enclosed in an enormous geodesic dome. Looking around that magnificent structure, it becomes clear that the dome is as every bit as shapely, pure, and perfect as the natural world it encloses, and it’s impossible not to admire and respect the poetic and protean mind that created it.