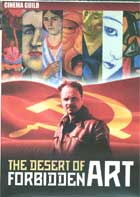

The Desert of Forbidden Art 2010

Distributed by Cinema Guild, 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800, New York, NY 10001; 212-685-6242

Produced by A. Pope and T. Georgiev

Directed by A. Pope and T. Georgiev

DVD, color, 80 min.

College - Adult

Art History, Soviet and Russian History, Uzbekistan, European Modernism

Date Entered: 12/02/2010

Reviewed by Andrew Jenks, California State University, Long BeachThis documentary follows a treasure trove of Russian art stashed in a remote desert region of Uzbekistan known as Karakalpakstan, where the art was hidden from Soviet censors. Getting there required crossing a vast desert—punctuated by fly-infested truck stops. Nukus was the principal city of this desert outpost—and the location of the museum housing this unlikely art collection. The art was forbidden, not because the artists were consciously anti-Soviet, but because they simply followed their own muses, irrespective of the dictates of the official Soviet artistic style under Stalin.

That such a collection of astounding avant-garde art could exist in Nukus amazed a New York Times reporter, who happened upon the museum during his time as a foreign correspondent covering Uzbekistan after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Uzbekistan is now an independent nation and was a republic in the former Soviet Union. The documentary is the answer to the question: How could such a collection end up in such a remote and dusty provincial backwater?

The answer begins with the collector Igor Savitsky. The son of a wealthy lawyer before the Bolshevik Revolution, he hid his aristocratic past from the communist authorities. He took a job as an electrician but dreamed of becoming an artist. He participated in archaeological digs in Central Asia in the 1930s, drawing what could not be photographed. He immersed himself in the ancient civilization buried in the sands near Nukus, painting landscapes while others on the dig slept in the midday heat. When art critics back in Moscow and Leningrad condemned his art as useless and lacking in revolutionary spirit, he was devastated. He destroyed all the works he had created and returned to Nukus. To his astonishment, he discovered the work of a group of Russian and Uzbek artists who had been attracted to the exotic locale for subject matter since the 1920s and 1930s. These artists imagined themselves to be the Russian equivalent of Gauguin, swapping in local Uzbeks for Tahitians. The Uzbeks were the descendents of an empire which in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries presided over one of the most impressive flowerings of Islamic culture and civilization. The artists attempted to find the spirit of modernity, paradoxically, in the supposedly ancient traditions and motifs of Uzbek culture. But the innovative and eclectic result received little support, predictably, from the Stalinist art bureaucracy, which was guided by the official artistic doctrine of socialist realism: happy tractor drivers, paeans to hydroelectric dams, portraits of Stalin. Indeed, many of the artists perished during Stalin’s purges, while others languished in poverty and obscurity. Savitsky made it his mission to collect and preserve their work.

After Stalin’s death Savitsky somehow managed to get authorities to finance a museum for his art in Nukus in 1966. How he did this remains something of a mystery – and one the documentary could have explored in more detail, since the museum suggests possibilities for the display of art in the Soviet period that conventional wisdom would reject. Distance from Moscow seems to have been one major reason he was able to create a tiny island of artistic freedom in a sea of soulless socialist realist artistic production. Savitsky’s shrewdness—and the stupidity of the censors—was another reason. He once managed to show a painting depicting inmates of Stalin’s prison camps (a taboo subject for artists from the mid-1960s until the Gorbachev era) by convincing the censors that the painting was devoted to images of prisoners in Nazi concentration camps.

Through the 1970s and until his death in 1984, he combed the collections of museums in Moscow for unorthodox art, which he managed to purchase with state funds for his museum! He sought out forgotten artists whose work did not fit the official doctrine and also convinced them to give him their work. Meanwhile, many official artists led double lives – painting official work but then painting what they really wanted to paint secretly. He would leave Moscow after his art hunting expeditions with piles of drawings and paintings and transport them across the desert to Nukus—1700 miles from Moscow, a trip he took 20 times. He was a master collector of unofficial art, operating under official cover as the director of a provincial museum, a kind of double agent. By the time he died in 1984, he had collected more than 44,000 items.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of the new nation of Uzbekistan have created new problems for the museum—both ideological and financial. Radical Islamists, inspired the by the example of the Taliban’s destruction of ancient and modern art have made the museum a target of their political attacks—especially since the museum’s director is a woman. But perhaps the greatest challenge is finding money to preserve the collection. The Uzbek government certainly does not have it. After the New York Times ran an article on the collection, private collectors from around the world arrived on private jets, with Euros and dollar signs in their eyes. It seems unlikely the museum will withstand for long the tantalizing offers from jet-setting art collectors, who are eager to make a new market at Sotheby’s in this hidden stash of avant-garde art. Indeed, surviving capitalism may ultimately be more difficult than the museum’s unlikely survival of communism.

While the Soviet system saw art as a political instrument—and thus as a target of political control—this documentary illustrates the limits of such political meddling, even in a system where the state had nearly universal power over both the production of art and its display. Students in a variety of courses will gain much from this documentary.

Political science and history students can contemplate the fate of art and artists in an authoritarian system. Art history students, meanwhile, will be intrigued by this heretofore unknown expression of the Russian avant-garde—which took the Uzbeks as a starting point for the fusion of European modernism and Central Asian Islamic culture.