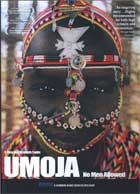

Umoja: No Men Allowed 2010

Distributed by Women Make Movies, 462 Broadway, New York, NY 10013; 212-925-0606

Produced by Elizabeth Tadic and Selene Alcock

Directed by Elizabeth Tadic

DVD, color, 32 min.

Sr. High - General Adult

African Studies, Anthropology, Domestic Violence, Sociology, Women’s Studies

Date Entered: 10/27/2011

Reviewed by Wendy Highby, University of Northern ColoradoRarely does a film so starkly and effectively document patriarchal social structure and the rebellion of women against it. Umoja: No Men Allowed is a quintessential tool for teaching students about gender discrimination within a particular cultural context. Filmmaker Tadic captures the viewpoints of both genders in this absorbing look at a divided African community. “Umoja,” the KiSwahili word for “unity,” is the name of a women-only village located in northern Kenya, near the Samburu National Reserve. The residents of Umoja are members of the Samburu tribe. Historically, the tribe’s economy has been based on nomadic pastoralism, but that has changed for the Umoja women.

The women’s separatism has a violent genesis. In the 1980s and 90s they were allegedly raped by British soldiers stationed at nearby military training bases. Their situation was worsened by the reaction of their husbands. The spouses blamed the women for the rapes and cast them out. The domestic violence and ostracism led the women to band together to reduce poverty and increase their security. They became entrepreneurs, selling crafts and sharing their culture with tourists on safari. With the leadership of Rebecca Lolosoli, the women united to create the village in the mid-1990s.

The Samburu men are envious of the women’s economic success. One kilometer from Umoja, they have located their own village, attempting to horn in on the tourist trade. In addition to the tourist-related business ventures, the women are using education to fight poverty and create change. They have started a coed primary school. Rebecca has been invited to help start more women’s villages. She travels to nearby communities and encourages the women to educate their daughters.

Tadic’s film is ethnographic and observational in style. On camera, the Samburu men defend their sexism. Leapora (one of the husbands) explains: “It’s the men who hold the law, not the women. . . . If we see a man beating up his wife, we like it because he’s knocking some sense into her.” Umoja’s leader, Rebecca, states her opposition to the patriarchal structure: “We don’t let them [the men] come and rule us again. We rule our village. . . . These men, they don’t want us to be empowered. . . . They don’t want women to have any rights.” Rebecca discusses the practice of female genital mutilation and explains frankly that she wants to change her culture.

The film is effectively edited to feature pivotal moments in village life. It documents the mediation attempts of the men’s envoy, Regional Chief Sebastian Lesinik. When he requests that they return to the men, the women rebuff him. True to the name “Umoja,” they express their solidarity and choose to remain gender-segregated. Tadic’s lens records moments of pure joy as the women partake of previously forbidden goat meat at a communal feast, laughingly swim in the river, and happily sing about freedom.

Umoja: No Men Allowed powerfully and succinctly documents the privilege inherent in patriarchy, the pain of social conflict, and the pleasure of breaking free. The film will undoubtedly spark discussions about culture, separatism, women’s rights, and social justice. It is appropriate for use in African studies, anthropology, sociology, and women’s studies courses.