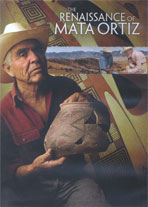

The Renaissance of Mata Ortiz 2011

Distributed by Mata Ortiz Productions, 12135 Mitchell Av. #348, Los Angeles, CA 90066

Produced by Scott Petersen

Directed by Scott Petersen

DVD, color, 54 min. plus addition 28 min. bonus

Jr. High - General Adult

Anthropology, Art, Art History, Latin American Studies, Sociology

Date Entered: 11/30/2011

Reviewed by Charmaine Henriques, Northwestern University Library, Evanston, IL“Juan Quezada is an inspiration. It’s an inspiration just to know someone like him without an education, without a professional career, he has accomplished all that he has. He is not only a person important to Mata Ortiz, but to Mexico. I think that what he’s doing can be a great influence to all artist. He continually strives to be innovative, and his designs are never copies. He is an example for artists and potters of Mata Ortiz.” Diego Valles, Mexican Artist

Spencer MacCallum, a social anthropologist from the United States is an addict. His drug of choice: yard sales. One day at a yard sale he was attending he saw a ceramic pot. MacCallum was so enthralled he bought the pot, brought it home and put it on his piano. Everyday he passed the piano and that pot spoke to him; so MacCallum began studying it. Around the same time he had invested in a gold mine in Deming, New Mexico. After a trip where he was checking on the mine, MacCallum decided to visit various yards sales without success. He remembered there was a second hand store called Bob’s Swap Shop that he always meant to visit. There, he surprisingly ran into three ceramic pots similar to the one that was on his piano. He bought the three pots for 15 dollars each. On his way home MacCallum thought about who crafted these ceramic pots. Initially, he believed a woman must have made them, since it is women who make pottery in indigenous cultures. Then Spencer got an idea, wouldn’t it be fun to find the maker of these pots? What he would say to her he did not know, but it did not matter, because locating the person would bring closure to the adventure of finding the pots. MacCallum and his wife went to Mexico, traveling from town to town in their Dodge truck, showing pictures of the pots. The next morning in Nuevo Casas Grandes while reviewing their notes, they noticed there was one place that was mentioned several times; Mata Ortiz. They departed for Mata Ortiz, where MacCallum finally encountered the creator of the pots, Juan Quezada.

When he was 14 years old and searching for firewood to sell, Juan Quezada noticed a covered cave. He peered into the cave and discovered a mummified couple with food and pottery; this became his inspiration. He did not want to fashion a copy of what he saw, he wanted to form pottery that was equal to what was in the cave. Juan examined the pottery, deconstructing it and eventually teaching himself how to create it. When he finally finished his first piece and showed it to his family and friends, they humored him but were not truly interested. Nevertheless, Juan would not be defeated. He remembered there were three men who arrived monthly to Mata Ortiz to sell clothing and devised a simple plan to get his work shown in the U.S. Juan gave each one of these men ceramic pots for free. They did not understand why Juan was giving them the pots and really did not want them, yet accepted the gift. However, when the men returned they wanted more pottery and was willing to pay Juan five dollars for each piece. Juan was ecstatic since he was making $2.50 a day carrying wood. After he realized his pottery was in demand he raised the price to ten dollars for each piece.

Juan was able to share his earnings with his brothers and sisters since financially they were not doing well. Then he told his siblings that he would teach them how to make pottery. At first, they refused but Juan told them there would be no more money, therefore they had no choice but to learn. Juan insisted if he could teach himself, then he could teach his family. He encouraged them and his siblings learned how to create pottery and then they taught others who taught others and the skills were passed on. Members of the community began to see that Juan and his family were able to earn more money by making pottery than picking fruit. Today, the main industry of Mata Ortiz is pottery and there are an estimated 450 potters who sign their own work. Juan’s pieces went from a few dollars to 1,000 dollars per piece.

Juan showed Spencer how he crafted the pots and Spencer was impressed. Spencer told Juan he would return in two months and he wanted him to experiment and create his best work. When Spencer returned to inspect the new pots they were no different from previous ones that Juan had made. In reality, Juan did not believe that Spencer would truly return. No one in Mexico took notice of Juan’s work and now here was this weird foreigner showing interest in his pots. Spencer also realized he did not give Juan the proper incentive. Spencer proposed an agreement; for six months he would provide Juan with a monthly check in order for him to experiment and pursue his art in any direction he wanted and if Juan agreed to these conditions anything he would chance to make would belong to Spencer. Juan agreed and when Spencer returned to Mata Ortiz to inspect Juan’s work, it was of an order of magnitude than what he did before. With each trip, Juan’s work improved substantially. Spencer dedicated himself to this project for six years. He promoted Juan and made contact with museum directors who then showed interest in Juan’s work. Juan was able to exhibit his creations and give workshops at institutions such as Princeton and the Rhode Island School of Design. From 1999-2000 Juan had 16 exhibits in the United States and Mexico. Also, in 1999 he received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes, which is the highest honor the country of Mexico can bestow on a living artist.

There is even a new sensation in Mata Ortiz named Diego Valles. Diego Valles and his family moved to Mata Ortiz from a tiny village named Santa Rosa. The family relocated to Mata Ortiz when Diego was about 12 or 13 years old in order for him to attend middle school. From the time he was in elementary school, Diego liked drawing and painting. He trained to become an engineer and received a B.A. in Mechanical and Electrical Engineering from the Instituto Technologico Superior de Nuevo Casas Grandes. Upon graduating, Diego was to sign a contract with an electrical company but decided to pursue his art. Diego’s work is of the school of Mata Ortiz, with its swinging dynamic, but his style is distinctive because he decided to cut out the design leaving open spaces (called black negative space) which is a breaking departure from Mata Ortiz pottery. Diego started creating pottery full time four years ago. Even though Mata Ortiz has a nice market, Diego still has to establish himself—which has been hard. Diego is not originally from Mata Ortiz and he is the only one in his family that produces pottery, therefore he is viewed as an outsider. Also, in Mata Ortiz many people work on the same product and competition is not welcomed. Nonetheless, in 2010 Diego Valles won the Premio Nacional de la Juventud, the top art prize the Mexican government awards a young Mexican artist.

The Renaissance of Mata Ortiz gives a detailed account of the relationship between Spencer MacCallum and Juan Quezada. The film is packed full of information and at times can be a bit overwhelming. Still, the audience obtains a great understanding of how the amazing encounter between these two men made a life changing impact on Mata Ortiz and potentially the northern region of Mexico. Initially, the film leaves a lot of questions unanswered, such as can the village sustain itself on one industry and how has the community been able to improve itself? But, questions like these and some historical information about Mata Ortiz is covered in the DVD extras. The Renaissance of Mata Ortiz is a fascinating film that tells the tale of how to very different individuals came together and started an artistic movement that saved an entire community.