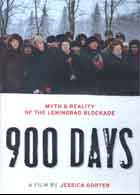

900 Days 2011

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Jessica Gorter

Directed by Jessica Gorter

DVD, color, 77 min.

College - General Adult

Soviet History, World War II, Myth and Memory, Cannibalism

Date Entered: 10/11/2012

Reviewed by Andrew Jenks, California State University, Long BeachThe Nazi siege of Leningrad began on September 8, 1941. It ended 874 days later, one of the longest and most destructive sieges in history. The Soviets won at the cost of more than 1 million soldiers killed, captured, or missing and more than 640,000 civilian dead. Nearly a third of the city perished—from disease, bombings, and starvation. Soviet propagandists—during the siege and afterwards—constructed a heroic story of perseverance and courage as part of a broader mythologizing of the war. That tale has served various social, political, and cultural purposes ever since. In the process, however, the real story was sanitized and simplified, hidden and censored to the point that even participants often preferred the mythological version (which at any rate was more ennobling than the real story). This fine documentary uses interviews with survivors and archival sources to help peel back the layers of myth and to reveal the historical siege that few survivors had ever discussed publicly.

Beyond the wrenching and tragic stories, the process by which the survivors blocked out their own memories of the blockade is the most fascinating part of the documentary. Many survivors preferred the heroic story over the one presented by the documentary evidence and by other survivors. The real memory—of cannibalism, of cowardice, of intense hunger—was simply too much for many to stand. Others experienced feelings of intense guilt because they had survived, making the heroic story even more attractive. One eyewitness wondered what was stronger: the government's suppression of the real experiences of suffering or the desire of the eyewitnesses to erase such a traumatic memory. In the end, both factors contributed to a condition of historical amnesia regarding the real account of the bloody siege.

But not all eyewitnesses preferred the sanitized, heroic tale. Many of the film’s subjects expressed bitterness and resentment that the political and social climate of the Soviet Union did not allow them to express their memories of the blockade, however horrifying. One woman remembered after the war that she was at school looking at pictures of old schoolmates. People would say: "That's the one we ate, that one was evacuated."

At the cemetery the corpses piled up—the ground was frozen too hard to bury them. Bodies were collected from the streets by cart and dumped in a pile (there is some excellent archival footage of street scenes from the siege). Many of those corpses were pockmarked with bloody cavities where people had carved out chunks of human flesh for a meal. During the documentary a narrator would occasionally read from secret police reports of cannibalism, of human flesh made into meatballs and sold in city markets, and of people murdered for their flesh.

Another survivor told a story about a cat she used to feed before the war. She remembered that it frequently came in search of food. During the siege she killed the cat with an axe, hacked it to pieces and ate it. This happened on her 11th birthday, just after her mother and sister had died from starvation and she had been made an orphan. As she related the story (her apartment was swarming with cats she had adopted from the streets), the camera man followed her to the wall of her apartment, where the survivor picked up a painting that had been facing toward the wall. It was a painting she had made years before: a self-portrait entitled, “We have to live after all.” It showed herself as a skeleton chopping up the cat. She told the interviewer she did not have long to live and feared the hereafter because she would burn in hell for her sins. Another survivor told the story of a mother with two children. The youngest, an infant, had died. The mother put the dead infant between the window panes, where it would stay frozen, and periodically hacked off pieces of flesh to feed the family by making a soup out of her daughter. She asked a priest if that was forbidden or if it was done out of love. She thought it was out of love but the priest disagreed.

These stories are not for the faint of heart. But the documentary will help students to understand the difference between memory and history, and between the heroic stories states often tell about wars and the suppression of the real events that did not fit their narratives. As such, this is an ideal documentary to show in any history class dealing with World War II or Soviet history.