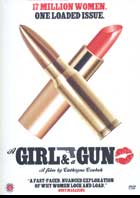

A Girl & A Gun 2012

Distributed by Collective Eye Films, 2305 SE Yamhill Street, Suite 101, Portland OR 97214; 503-232-5345

Produced by Cathryne Czubek and Jessica Wolfson

Directed by Cathryne Czubek

DVD , color, 76 min.

College - General Adult

Criminology, Psychology, Sociology, Violence, Weapons, Women’s Studies

Date Entered: 08/14/2013

Reviewed by Wendy Highby, University of Northern ColoradoA Girl & a Gun begins with a rhetorical question: “We live in a culture where guns are symbolic of masculinity and American identity; where does that leave women?” The film starts by visually exploiting the psychosexual symbolism of women’s gun use and ownership. It manipulatively juxtaposes red stiletto heels with a gun and cuts to shooters with manicured nails painted bright red. But don’t be fooled by A Girl & a Gun’s cheeky introduction and title. While the documentary begins with playful images and theme music, it provides a serious overview of women’s use of guns. Transitioning rapidly out of this symbolic territory, the movie focuses upon the realities and consequences of gun use and ownership for women. Academic talking heads present a brief social history, exploring representations of women and guns in popular culture and the media, spanning more than a century. A greater portion of the film tackles both psychological and sociological aspects of women and firearms in an anecdotal manner, through candid personal interviews.

The gun owners interviewed include: Violet Blue, a San Francisco journalist; Deb Ferns, a gun safety instructor; Emily Blount, an Olympic skeet shooter; and Rosemarie Weber, a former Marine Corps Master Gunnery Sergeant. These women and other interviewees express a variety of purposes and motivations for gun ownership, including following family tradition, enjoyment as a sport, and the need for protection. One viewpoint missing from the film is that of women in law enforcement. Interviewee Robin Natanel provides the central narrative thread. A tai chi instructor, she purchased a gun to protect herself from an abusive ex-boyfriend. The interviews with Robin provide insight into the psychology of gun ownership. She shares her ambivalence about actual use of the weapon with a self-defense instructor. They speak about women’s socialization to be less assertive, and about the discovery of inner strength and use of one’s voice as a deterrent. Interviews with perpetrators and victims of gun violence provide a cautionary counterpoint. An inmate of the Louisiana Correctional Institute, Karen Copeland, shares her experience as a convicted felon. Victims’ Rights Activist Stephanie Alexander is interviewed, as well as her daughter, Aieshia Johnson, who is paraplegic as a result of gun violence. Alexander explains that her activism is a form of healing therapy. A particularly strong vignette, potentially helpful for anyone studying victimology and/or counseling with violence victims, is a segment in which immediate family members of victims frankly discuss the unhelpful platitudes they’ve heard.

Several of the academics featured in the film have authored books about the social history of women and guns: Mary Stange, Gun Women: Firearms and Feminism in Contemporary America (Professor of Religious Studies at Skidmore College); Laura Browder, Her Best Shot: Women and Guns in America (Professor of American Studies, University of Richmond); and Nancy Floyd, She’s Got a Gun (visual historian and artist). The social history covers a wide span, including Annie Oakley, 1920s pulp fiction, and 1960s radical left politics. The influence of feminism of the 1970s is discussed, as are the two opposing strains of thought: one advocating that women be just as tough as men, the other yoking pacifism with feminism. A representative of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, Jennifer Bishop Jenkins, speaks of the media push in the 1980s to portray women as victims. She explains that handgun manufacturers started exploiting these fears in their marketing toward women.

The film ends with a feminist statement from one of the academics: “a gun is not going to get you day care and equal pay.” So while the film tries to cloak itself in a hip, sometimes almost Tarantino-esque breeziness, its viewpoint is ultimately feminist, and its intention is didactic and serious. The documentary does not provide statistical data, results of peer-reviewed studies, or a preachy attitude. It does put forth interview content that is revealing and powerful and it presents a variety of viewpoints. The film is particularly apt for undergraduates and would support curriculum in sociology, criminology, victimology, women’s studies, psychology, and cultural studies. It would be especially effective as discussion starter. Despite its glib title, A Girl & a Gun is a serious amalgam of social history and candid personal stories regarding women and gun ownership; it is sure to pique students’ interest.