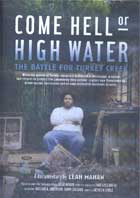

Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek 2013

Distributed by Bullfrog Films, PO Box 149, Oley, PA 19547; 800-543-FROG (3764)

Produced by Leah Mahan

Directed by Leah Mahan

DVD , color, 56 min.

General Adult

Growth of Cities and Towns, Activism, Hurricane Katrina, British Petroleum, Environmental Justice

Date Entered: 10/02/2014

Reviewed by Andrew Jenks, California State University, Long BeachThose who sing paeans to progress almost always remain silent about the people who supposedly stand in its way. This documentary tells the story of a group of activists struggling to save their small Mississippi community of Turkey Creek from the bulldozer. In the last three decades the city of Gulfport has targeted the community – as well as the vital wetlands on which it sits—to make way for golf courses and casinos.

The central hero of the film is Derrick Evans, a Boston teacher and civil rights historian, with local roots in Turkey Creek. His friend, the filmmaker, followed his return to record his epic battle to save a small community, riparian habitat, and sacred burial ground of former slaves (already partially destroyed to make room for an apartment complex). The filming took place over more than a decade starting in 2001, thus conveying the reality of constant struggle, setbacks, minor victories, and new disappointments.

Former slaves created the community of Turkey Creek after the Civil War to make a new and prosperous life near the Gulf Coast. Painstakingly saving their money, they bought 80 acres each. It was a secluded and self-sufficient community, created in a wilderness before the city of Gulfport was established around 1900 as a terminus for Mississippi timber. By the 1950s, however, the urban world had begun to encroach, relentlessly expanding northward toward Turkey Creek. By the 1990s Turkey Creek was surrounded by Gulfport whose economy had been transformed by the newly legalized gambling industry.

The film tells a classic David-versus-Goliath story: the 70,000 residents of Gulfport and their interests supposedly associated with Mississippi’s Gulf Coast future and the 400 residents of Turkey Creek, mostly elderly. For most of the film Goliath seemed to be winning.

Meanwhile, the ongoing destruction of the wetlands has aided development interests. Shrinking wetlands reduce the ability of the land to absorb heavy rains, causing the creek to rise far more than it ever did in previous decades and flooding the homes of residents.

What is remarkable about Turkey Creek is the surprising unity of its citizens in the face of lucrative buyouts. Nearly all rejected money offers to move, confounding not only the developers but the very essence of the capitalist system, which is based on the proposition that everything can be reduced to a sales price. The residents’ refusal to commodify their lives stands at the core of resistance and activism at Turkey Creek. It so enraged the powers that be that the white mayor of Gulfport referred to opponents of development plans as “dumb bastards.” His comment suggests the racial as well as economic tensions involved in the struggle at Turkey Creek. The developers and their political supporters interviewed in the film are exclusively white, probably descended from former slave owners, and the residents of Turkey Creek are black, descendants of slaves.

The film follows the roller-coaster emotions of the activists as they swing from elation at apparent success to despondency after yet another unanticipated failure. Their initial attempt to classify the community as an historic preservation site failed, so they shifted to organizing an urban waterway – a greenway – through the purchase of land rights all along the Creek as a buffer zone between the Creek and the city. With the help of the Sierra Club and its legal filings for environmental impact statements, the developers withdrew their development permit applications. And just as it seemed that plans for a greenway were coming to fruition, Hurricane Katrina hit, essentially doing the bulldozing that developers had planned.

Katrina gave momentum to those who argued for a new and developed vision of the Gulf, following the pattern of gentrification of New Orleans, and the replacement of black populations with white ones. It is a sad and familiar tale throughout the Gulf region affected by Katrina. Recovery funds from the federal government were used to bulldoze wetlands and create new developments. State and federal authorities lifted bans on the removal of wetlands, without providing any public notice, in order to facilitate a certain kind of development that favored hotels, golf courses, and casino operators. Development interests, meanwhile, took the lion’s share of recovery money even while thousands of people made homeless by the storm were still living in FEMA trailers.

The story at least has a partially happy ending. Tapping into Civil Rights protests traditions, the citizens of Turkey Creek, after more than a decade of petitions, finally were able to secure a place in the federal historical register as well as the rights to a greenway along Turkey Creek protecting it from development. It is now, at least, an island in a sea of golf courses and casinos, a place that maintains, if only tenuously, a connection to both the human settlers of the region and to the environmental past. The film ends with the 2010 BP oil spill disaster – the largest man-made environmental disaster in U.S. history. How that will impact Turkey Creek is unclear, but Evans decided that he must again delay his trip back to Boston to get his affairs in order and continue the struggle on behalf of the people and land of Turkey Creek.

This is a well-told story about the clash of interests and ideals that accompany development. On the one side are the representatives of the new economy, who invariably justify their dominance by referring to themselves as agents of positive change. On the other side are the representatives of the older economy who lack the money of their opponents and are constantly characterized as enemies of progress. These clashing economic interests also align with historical racial divides, pitting rich and white development interests against the poorer black residents. The film succeeds in its aim to provoke maximum outrage in telling its story of greed, grass-roots activism, and racism. Even if Turkey Creek disappears, like so many thousands of similar communities, the film at least preserves its memory from the bulldozer of historical amnesia.