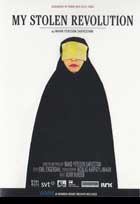

My Stolen Revolution 2013

Distributed by Women Make Movies, 115 W. 29th Street, Suite 1200,New York, NY, 10001; 212-925-0606

Produced by Nahid Persson Savestani

Directed by Nahid Persson Savestani

DVD , color, 75 min., Swedish and Farsi with English Subtitles

High School - General Adult

Iran, History, Women’s Rights

Date Entered: 05/13/2015

Reviewed by Marie Letarte Mueller, Director, Bigelow Free Public LibraryThe producer, Nahid Persson Savestani, escaped Iran with her daughter a few years after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. She had been an active pro-democracy protestor—first against the oppression of the Shah, then against the worse oppression of the Ayatollah. Images of uprisings from 1979—full of colors—and those of the 1980s (when women were covered in black chadors) make a stark contrast at the beginning of the film.

Nahid escaped to Sweden, but still held memories and guilt about not staying behind. Her brother, Rostam, had been arrested and tortured to reveal her whereabouts, but he refused and was executed shortly before she fled the country.

Thirty years later, she started to look for the women with whom she had fought. One by one, the viewer sees an image of the names being crossed off as news of their death or execution (far too frequently, the latter) reached her. Finally, she reached Shahin, a woman who had been her mentor in the revolution, living in San Francisco. This reunion started to open up old feelings in Nahid as they spoke about the past—meeting in secret, sewing clothes, mass executions, and fleeing the country. Shahin still had a pair of shears she had carried with her from Iran.

Nahid’s connection to Shahin was broken when she discovers her mentor’s conversion to Islam. She felt that their struggle against the oppression was negated and minimized by Shahin’s embrace of the opposition.

She returned to Sweden with more names from the revolution. These women had all served years in prison as political prisoners. Their reminiscence and memories of torture, conditions, guards, executions, and smells are painful to hear—both for Nahid and for the viewer. Nahid continued to feel guilt because she left her brother and because she escaped.

The women’s stories are heart wrenchingly familiar to anyone who has read about political prisoners or the Islamic Revolution, but it doesn’t make them any less poignant. The fact that they were willing to meet with Nahid in front of cameras and talk about their experiences (like a girls’ weekend reunion) says a lot about their bravery and their strength.

All of these women have scars, both physical and emotional, but they’ve managed to move on and can still laugh. The film should make the viewer think about her or her own life in a free country in parallel to their lives in prison. Anyone who remembers the 1979 Islamic Revolution may feel a stronger connection to these women.