The Farmer and the Chef 2015

Distributed by Filmakers Library, 124 East 40th Street, New York, NY 10016; 202-808-4980

Produced by Michael Whalen and Nicole C. Whalen

Directed by Michael Whalen

DVD, color, 65 min.

General Adult

Agriculture, Cooking, Documentaries, Food, Sustainability

Date Entered: 06/19/2015

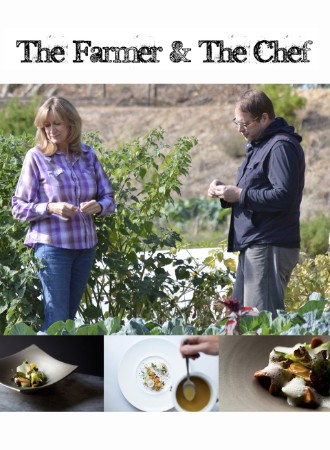

Reviewed by Andy Horbal, University of Maryland LibrariesChef David Kinch founded the restaurant Manresa in Los Gatos, California in 2002. It received two Michelin stars in 2007 and has continued to rack up accolades since, including a James Beard Award for Best Chefs in America for the Pacific region for Kinch in 2010 and a coveted spot on the S. Pellegrino World’s Best Restaurants list. The Farmer and the Chef celebrates Manresa’s 10-year anniversary by exploring its relationship with Cynthia Sandberg’s Love Apple Farm, which a parade of current and former employees describe as the most important development in the restaurant’s history.

Kinch and Sandberg met when she went to Manresa for her birthday. A mutual friend had tipped Kinch off to the fact that she was a talented amateur tomato farmer, and he came to her table to introduce himself and ask if he could sample her wares. He was so impressed that he used Love Apple Farm as his exclusive supplier for Manresa’s annual tomato dinner later that year. Not long afterward, Kinch called Sandberg for advice on starting a kitchen garden. She suggested that Love Apple could produce vegetables for him instead, and they began working together in 2006. By the time Love Apple moved to a bigger location in 2010 (which is documented in the film) it was providing Manresa with all of its produce.

A major factor in Kinch’s and Sandberg’s decision to partner with one another is their shared commitment to biodynamics, an approach to agriculture developed in the 1920s which combines conventional organic farming practices (crop rotation, avoidance of artificial fertilizers and pesticides, etc.) with techniques designed to harness the power of celestial and spiritual forces. The film doesn’t shy away from the more unusual aspects of biodynamics: one of its centerpiece scenes is a five-minute sequence in which Sandberg shows farm apprentices how to make a “preparation” for soil improvement, a process that involves burying fresh cow dung in a cow horn underground for six months in the fall and winter “when the earth breathes in” and stirring it in warm water for an entire hour before applying it to planting beds in small doses. Mostly, though, biodynamics is depicted as just the means to an end, growing great vegetables.

What’s more interesting is the way the film presents Manresa as the result of a collective vision. Contemporary American popular culture holds a Romantic view of chefs, and restaurants are often seen as monuments to their individual genius. David Kinch is inarguably the driving force behind much of Manresa’s success, and at one point he does describe it as “a distillation of all [his] experiences.” However, he also talks about the vital role servers and other front-of-house staff not under his direct supervision play in achieving his goal of creating the “quintessential California dining experience,” and notes that when Love Apple became Manresa’s exclusive supplier of produce it also effectively began writing the menu, since the restaurant had no choice but to use what was ready or let it go to waste. Scenes in which chef de cuisine Jessica Largey develops recipes with Kinch and talks to the farmers at Love Apple show her as being a significant influence on the Manresa’s direction as well. The lesson is that a successful restaurant inherently represents more points of view than just that of the chef, no matter how great his or her celebrity.

The Farmer and the Chef will remind many viewers of the Netflix documentary series Chef’s Table. Not incidentally, both feature subjects who charge a lot for their services: dinner at Manresa, for instance, costs $198 per person, plus another $158 each for beverage pairings. As both Kinch and Sandberg note, bespoke vegetable farming is not cheap and it’s only possible if restaurant customers help share the expense. The fact that few people can afford to pay this much for a meal doesn’t diminish the appeal of these films, though. It’s worth remembering that many previous revolutions in the way we eat like coursed dinners (appetizer, entrée, dessert) and the fork started with the wealthy and only later became widespread, so Manresa’s approach may be a harbinger of a broader change to come. More importantly, the idea that food can convey a strong sense of place is one chefs everywhere can adopt, even if they can’t start their own year-round kitchen garden. Lastly, the Food Network has proven that there’s something enormously satisfying about watching delicious food being prepared, even if we can’t ever eat it ourselves. For all of these reasons, The Farmer and the Chef is a great addition to media collections as a fine example of a movie in which “educational” and “enjoyable” happily converge.