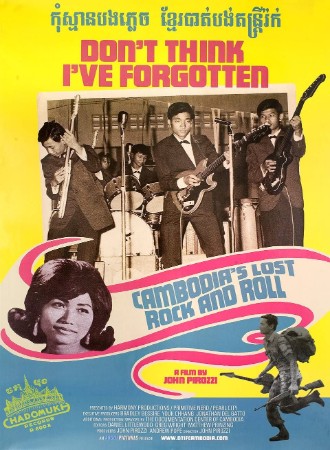

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll 2013

Distributed by Argot Pictures

Produced by John Pirozzi and Andrew Pope

Directed by John Pirozzi

DVD, color, 106 min.

Middle School - General Adult

Music, Sociology, Political Science, History

Date Entered: 07/01/2015

Reviewed by Anne Shelley, Music/Multimedia Librarian, Milner Library, Illinois State UniversityDon’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll explores the country’s unique flavor of rock and roll music before, during, and after the Vietnam War. The journey that music undergoes in the film is a heartbreaking one, from a ruling family in the 1950s who ordered an orchestra formed by ministries across the country to the Khmer Rouge’s near obliteration of Cambodian musical culture. We get a brief overview of native Cambodian music and then the film then spends a good deal of time on popular music influenced by the West, and finally how Cambodian musicians and their craft weathered the 1975-79 regime and genocide.

The film is lengthy but filmmaker John Pirozzi does a fantastic job of threading music through every point he makes. We see fabulous footage of dancers in native Cambodian dress, and music being played at ceremonies and celebrations. Striking cinematography shows the current dilapidated state of the National Radio, where performers covered in the doc—Sinn Sisamouth, Ros Serey Sother, Huoy Meas, Baksey Cham Krong—recorded. Later on, music brought over by American soldiers in Vietnam, like Santana and Little Richard, flavored Cambodian popular music. In the early 1970s, civil war began between the US-backed Cambodian government and the Khmer Rouge. This development led to a higher number of nationalistic songs, and the National Radio forced musicians to produce patriotic music rather than love songs; however, the National Radio allowed playing of foreign music (James Taylor), and Cambodian artists started mixing lyrics of popular American songs with their native language. Cambodia became an agricultural slave nation for several years after the war; music was labor songs sung by children working in the fields, and foreign music was forbidden. If recordings were found by the Khmer Rouge, people were forced to burn them. And when people were cautiously repopulating Phnom Penh in 1979, some knew it was safe to return because they heard singers on the National Radio. (A moving, final scene of the doc is a haunting recording of “Oh, Phnom Penh”—a song about the survival and importance of the Cambodian capital—with footage of the ruined city.)

Throughout the documentary, we are treated to many long stretches of songs that epitomize a style, a singer, or a theme, with newly-shot reenactments, footage of performances from the 60s or 70s, paintings, or tastefully animated graphics running in the background. The film is smartly edited; transitions and background images are a mixture of footage of Cambodian rock singers in the 60s/70s and striking cover art. And there is interesting manipulation of graphics throughout –visual elements are separated from cover art and animated. It’s not cheesy or overdone, but just right. There are interviews with several musicians who were active performers before the War. At the end of the doc, people we had been hearing from the entire film revealed how their entire families, save for themselves, had died in the Pol Pot regime. This film is captivating, moving, and informative—it’s an outstanding production that I highly recommend.