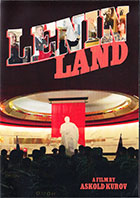

Lenin Land 2013

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Askold Kurov

Directed by Askold Kurov

DVD, color, 52 min., Russian with English subtitles

General Adult

Soviet Union, Russia, History, Museums

Date Entered: 10/15/2015

Reviewed by Andrew Jenks, California State University, Long BeachOn the occasion of the October Revolution’s 50th anniversary, Leonid Brezhnev in 1967 sought to legitimize his power with the legacy of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. It wasn’t the first time Lenin’s lifeless body performed political service. Lenin became a kind of fig leaf to hide political sins and failures, and to promote devotion to his live comrades, when his pickled remains were put on public display in 1924 (and where they have remained ever since). However, the 50th anniversary marked an unprecedented production of Leniniana in posters and sculptures in every Soviet town and in the general tendency to transform Lenin into the font of all wisdom. This fascinating documentary recounts the culmination of this process of mummification: the opening in 1987 of a museum devoted to Lenin on the estate where he lived, worked and died. Ironically, the museum’s opening coincided with the collapse of the system over which Lenin had presided.

The 1990s were understandably tense times for Lenin’s acolytes. It seemed as if the Lenin cult, and Lenin’s body quite literally, might finally be given the proper burial that his widow had demanded, against Stalin’s wishes, back in 1924. But Boris Yeltsin lacked the political will to attack the cult, which had insinuated itself in unexpected ways into the fabric of post-Soviet Russian culture. A quarter century later, Lenin has been joined to the new, post-Soviet revival of Russian Orthodoxy, which has benefitted from former communists (and KGB officials such as Vladimir Putin) swapping the old official communist faith for the new/old Orthodox faith.

The central figure in the documentary is the museum’s curator. She appears in the opening scene after a ceremony inducting a boy into the ranks of the Young Pioneers – the Soviet equivalent of Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts – with the pledge to be loyal to Lenin’s principles, which supposedly amalgamated and synthesized all the best aspects of human thought. The children themselves – young teenagers – mostly act embarrassed. Meanwhile, the adults remember fondly their own initiation rites in the Soviet days, striking an attitude of seriousness and solemnity. As the curator reminded the children, the Lenin museum was designed as a temple whose purpose was to make Lenin’s ideas eternal. She also saw her museum, facing constant budget cuts, as an essential antidote to the rampant corruption and inequality of post-Soviet Russia.

The film takes an ironic and understated approach to the topic, allowing the absurdities and contradictions of the living Lenin cult to express themselves. In one scene elderly women visiting the museum speak directly to Lenin’s bust, as if they were praying to Jesus. An Orthodox church operates right next to the museum, fused to the Soviet past and to Lenin as a new faith for young and old alike. The mundane activities of cleaning, maintaining the exhibits, and making sure the technology works make up much of the documentary. Museum workers wipe the dust off the nose, eyes and lips of Lenin’s alabaster bust, providing a glimpse into the prosaic and profane tasks that are required to operate a political and religious shrine, a temple of eternal Lenin. Most telling is the difference in attitudes between the generations. The older generation revere Lenin, holding his every act and moment in life to be sacred. One of the museum workers and tour guides presents Lenin as the embodiment of the “vibrations of Christ,” the struggle between the soul and material world and the victory of the former. “And this truth of the Lord was with the Bolsheviks,” she told the visitors, as she completed the link between Jesus and Lenin. Most of the younger generation carted to the museum seem uninterested, amused or even embarrassed by the obsessions of their elders, yet perhaps their elders struck similarly disinterested poses at their own initiation ceremonies back in the 1970s or 1980s. Meanwhile, the remaining museum workers debated the nature and purpose of the museum – to maintain it as a shrine to the “Mohatma” Lenin, as one worker put it, or to downplay the cultic aspects and focus on the actual life and times of Lenin.

This is a funny, moving, profound view into the past, present and future of the Lenin cult. The contested nature of the cult reflects, in microcosm, broader debates about the meaning and significance of the Bolshevik Revolution for today’s Russia. As the Soviet propaganda posters put it: “Lenin lived, Lenin lives, Lenin will live!”