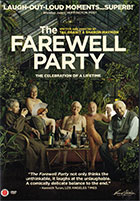

The Farewell Party 2014 (released in the U.S.A. in 2015)

Distributed by First Run Features, 630 Ninth Avenue, Suite 1213, New York, NY 10036; 212-243-0600

Produced by Samuel Goldwyn Films and Beta Cinema

Director n/a

DVD , color, 95 min.

College - General Adult

Aging, Death and Dying, Euthanasia

Date Entered: 12/01/2015

Reviewed by Sheila Intner, Professor Emerita, Graduate School of Library & Information Science, Simmons College GSLIS at Mt. Holyoke, South Hadley, MAThis is not a film for sissies. It tackles a tough subject directly and is sure to offend some viewers, who cannot help but be conflicted over intense desires to help friends in need but also obey the moral law of both state and religion. This is a film about euthanasia—a euphemism for mercy killing that fails to express either its kindness or its horror. That the film also portrays the lives and plight of the very old with humor and tenderness is one of its strengths. That it is entirely a work of fiction—not even bordering on docudrama—is one of its weaknesses.

Spoiler Alert! The story focuses on a group of elderly Israelis living in a Jerusalem retirement community. Yana’s husband is a terminal patient who is suffering unbearably and longs to end the pain. Among many close friends are Yehezkiel, once an inventive machinist who is married to Levana, sweet and pretty despite her age, though she is in the early stages of dementia, and Dr. Daniel, a veterinarian. Dr. Daniel has a stash of the drugs he once used to put down ailing animals, and Yehezkiel designs a machine that enables someone to administer them in a fatal dose. At Yana’s behest, they help her husband end his life. Only Levana protests, telling Yehezkiel and the others it is murder, although she keeps silent about it. But, when the deed is done, it leaks to others, and several people faced with similar agonies beg the group for help, threatening exposure if they refuse. They deny everything and try to stop the rumors, but eventually help more sufferers die.

As the days pass, Yehezkiel doesn’t allow himself to admit that Levana is descending into dementia. She acts more and more strangely, adding salt instead of sugar to a batch of cookies she is baking with her granddaughter, setting their kitchen on fire, and, finally, appearing nearly nude in the community’s dining room. She swears she will never leave her apartment and face the community again, but Yehezkiel persuades her to go out with him late in the evening to the greenhouse. There, the members of the group are having a little party, drinking and laughing, all entirely nude.

As the film draws to a close, Levana recognizes that she is losing her mind. She agrees with her daughter that she must move to a nursing home and visits one recommended to her. Patients sit in rows of wheelchairs facing a window wall without speaking or moving, and she and Yehezkiel are horrified at the sight. That night, she begs Yehezkiel to end her life with his machine.

Technically, the film is first rate—the cast is outstanding; the camerawork and editing are excellent; the story moves well. The only drawback is the subtitles, which are dreadful. The film is in Hebrew with English subtitles, so good subtitles are absolutely essential. The letters are so small and remain on the screen so briefly that this reviewer had to sit on top of the screen to view them and, even so, missed chunks of dialog. This is a shame for a resource that could enhance courses in and discussions about end-of-life issues—a subject that lacks an abundance of resource material.