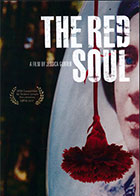

The Red Soul 2017

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by

Directed by Jessica Gorter

DVD, color, 90 min, Russian with English subtitles .

College - General Adult

Stalinism, Historical Memory, Russian Society, Communism, Nostalgia

Date Entered: 07/30/2018

Reviewed by Andrew Jenks, California State University, Long BeachWikipedia defines nostalgia as a, “sentimentality for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations.” How odd, then, to associate such happy feelings with the life and memory of one of the most brutal dictators in human history, Joseph Stalin.

In this brilliant and fascinating film, the award-winning documentary filmmaker Jessica Gorter explores nostalgia for Stalin and his era in modern-day Russia. Red Soul builds upon Gorter’s examination of the tension between memory and history in her masterful account of the 900-day siege of Leningrad in 900 Days. That film showed how the memory of the past in post-Soviet Russia was driven to a large degree by a fondness for Stalin, combined with a reluctance by both the state and everyday citizens to remember uncomfortable and sometimes shameful moments. Picking up on the thread of her earlier work, Gorter has focused on exploring the enduring cult of Stalin more than 60 years after his death, which has filled the vacuum of silence regarding Stalin’s terror and oppression.

Gorter has a knack for getting into the intimate spaces of people’s lives. Some of her subjects are wary of being provoked, accusing her of “provocation” by asking them to express their views on Stalin. But they express those views anyway, providing a dramatic counterpoint to interviews with the victim’s of Stalin’s oppression who struggle in Putin’s Russia to resurrect and preserve the memory of the terror. Ultimately, the latter are no match for the forces of nostalgia for Stalinism, which is aided by the Russian’s state refusal to search for the buried remains of victims – both the physical remains, in isolated places in the far north of Russia where prisoners perished in unmarked graves by the tens of thousands, and the records of those who perished, mostly locked away and inaccessible in secret police archives.

Over nearly two decades of rule, Putin has encouraged a more positive view of Stalin as a tough but effective manager and organizer. When the arrest and execution of innocent people is mentioned at all, it is dismissed as the inevitable byproduct of a tough but necessary crackdown on lawlessness and national security threats. The film casts a wide net, interviewing young and old people alike. Business-minded Russians can see in this image of Stalin the tough manager a model for survival in the rough and tumble world of capitalist Russia, while the older generation can dream of Putin, as a latter day Stalin, as someone who will arrest and vanquish the supposed enemies who have destroyed their livelihoods and the glory that was once the Soviet Union. As one elderly woman exclaims – while her friend urges her to keep quiet since the cameras are rolling: “If only Stalin were here.”

One historian and archivist featured in the film argues passionately for the need to recover and promote the memory of those who suffered at Stalin’s hands, but he is well aware of the overwhelming odds that he faces. He estimates that there are perhaps one hundred people actively researching and preserving the memory of Stalinist oppression, and they face increasing hostility and bureaucratic stonewalling from local and central government authorities.

One thing the video points out is that historians have documented Stalin’s terror, even if access to archival sources has been sporadic. Faced with the unpleasant facts of Stalin’s terror, versus the nostalgic and heroic image of Stalin as Russia’s industrializer and vanquisher of enemies, people prefer the nostalgic version. For example, sociologists in Russia have conducted surveys on views of Stalin since the Gorbachev era, and they have shown an astounding increase in the positive view of Stalin from 8 percent in the late 1980s to 52 percent in 2017, and this despite the publication of thousands of documents testifying to the brutality and injustice of Stalin’s politics. The nostalgic view of Stalin has developed in inverse proportion to the view of the 1990s flirtation with American-style democracy and capitalism as an unmitigated disaster that would have been even more disastrous if not for Vladimir Putin’s perceived leadership in the following decade.

Combatting this nostalgic turn will require something very unlikely: a compelling state initiative to make remembrance a part of the culture, by funding the search for unmarked, mass graves, by introducing the subject of Stalin’s terror into a history curriculum that now favors the positive view of Stalin as a tough manager, and by providing much more access to secret police archives. But that seems highly unlikely given Putin’s projection of himself as the mirror image of Stalin-the-tough manager, and perhaps more importantly because of the popularity of that image.