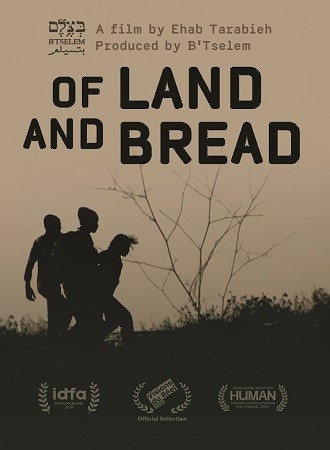

Of Land and Bread 2019

Distributed by The Video Project, 145 - 9th St., Suite 102, San Francisco, CA 94103; 800-475-2638

Produced by B'Tselem and Ehab Tarbieh

Directed by Ehab Tarabieh

Streaming, 90 mins

High School - General Adult

Arab Israeli Conflict; Film Studies; Human Rights

Date Entered: 08/05/2020

Reviewed by Michal Goldman, Documentary Filmmaker; Member-Owner, New Day Films (https://www.newday.com/filmmaker/175)In 2007, the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem launched its Camera Project, providing small video cameras to Palestinian volunteers living in the West Bank who agreed to document their daily lives under the Israeli occupation. This much information is presented on a title card, white letters on a black background, at the beginning of the film.

In 2010, a young filmmaker, Ehab Tarabieh, joined the Camera Project, and in 2016 he became its director. The following year, B’Tselem turned the first ten years of documentation over to him to make into a feature-length documentary. Recognizing that the power of the finished film would lie in the original purpose of its material, Tarabieh went to great lengths to preserve its authenticity, so that we, as viewers, would have no doubt and no way to doubt that what we see on the screen actually occurred.

Tarabieh accomplishes this using two seemingly incompatible kinds of material. Of Land and Bread opens with exactly the kind of unstable, swinging, unfocused image that most filmmakers cut out; the person who is filming has turned his camera on before setting it down in a field that he is about to plant; we see him come out from behind the now-stable camera and get to work. Unlike most filmmakers, who want us to forget about the mechanics that have produced the image we are seeing, Tarabieh reminds us that these cameras are being held by individuals, and that what is going on behind the lens is as important as what is going on in front of it. For this reason, the individual shots tend to be long, without internal edits; we are watching something unfold in real time.

A few cameras are mounted high up on walls to produce surveillance or security images with the date and time displayed in one corner of the frame. Here the means production is the opposite of the hand-held material, but the outcome is the same: because what the camera records is free from human intervention, there is no way to doubt its veracity. The first such material records a small alley with the time stamp 11/02/16 17:56:48. At first nothing happens apart from the seconds ticking over. Then a few boys enter lackadaisically from screen left, bending down to pick up small stones as they walk along. A car drives in from screen right, the boys scatter, soldiers enter the frame in pursuit, they knock one of the slower boys down, he gets up and raises his hands in the air, he looks to be about ten, he’s wearing glasses. Cut to black.

The film consists of seventeen such scenes plus a prologue and an epilogue, each ending with a cut to black. Off camera, the West Bank has seen wars, betrayals, bombings, and acts of terror that reverberate through this film like background noise. But what we are actually watching is, in Palestinian terms, nothing extraordinary: it is merely the relentless threat of violence inherent in daily life. And it’s exactly this everyday quality that makes these scenes so horrifying. The title cards, always white letters on black, that appear before each hand-held scene, feel almost familiar – “Night and Day,” “The Boy and the Stone,” “Bedtime Story” – and create certain expectations about what will follow. The tension builds through the way what follows will subvert our expectations.

Two large themes develop, closely intertwined. The first is the theme of harassment and loss of control. The second is the theme of resistance.

Loss of control plays out in the invasion of private space by Israeli soldiers who are assigned the tasks of occupation. In “Night and Day,” a videographer records a group of soldiers who have gathered on his roof late at night. From behind the camera he asks, “Why are you here at night?” They don’t answer and they don’t leave. His wife shouts at them, “There are children here. Go Home!” These soldiers, most of them very young, come into people’s homes, mug for the camera, are embarrassed, demand documents, are sometimes unsure of themselves, round up sleepy children, find nothing, trail off down the stairs – and come back the next day, always with the implicit potential for violence. Sometimes the violence can’t be managed; a security camera placed high on the wall of a shop’s small storeroom records a group of soldiers rushing into this narrow space, knocking the man down who is working there, kicking him, and dragging him out by the feet. Watching this we are likely to ask ourselves what he did to merit this treatment before the scene began. And then we are likely to tell ourselves that it doesn’t matter, because nothing merits this treatment.

The videographer who sets up his camera at the beginning of the film records a settler who comes into the field he is planting to announce that he wants to claim half the field for himself. Ultra-religious settlers, many of whom immigrate to the West Bank from the United States, act with impunity knowing that the Israeli military must back them up. The Palestinian asserts his legal ownership: “This field was my father’s and I have papers to prove it.” The settler, who is operating on another plane, responds: “This is the land of Israel, blessed be God. The big Messiah will come any minute. He’ll blow a big trumpet, and you’ll be our slaves – but only if we want.” In any circumstance we regard as normal, this response would be considered either grotesque or insane. But not on the West Bank, where this kind of response is protected by the military, as both the Palestinian and the Israeli know very well.

Israeli soldiers on patrol harass children, some of whom are quite small, because children sometimes throw stones at them. The Palestinian videographers use their cameras to record this harassment, sometimes filming out in the open, and sometimes filming unseen from behind their windows. When the soldiers, most of them very young themselves, don’t think anybody is watching, they terrorize children with quick kicks or blows. The effect of this brutalization on children is a question that becomes explicit in the long final scene, called “Bedtime Story.”

The threat of violence extends to women as well. In a scene called “The Errand Boys,” a woman documents the detention of two small boys accused of stone throwing. Pleading for their release from behind the camera, she says to the soldiers, in English, “They are very small. They are kids,” and then to the children, in Arabic, “Why are you being detained?” At first the soldiers flirt with her, pose for her, take her picture too. But eventually one comes up to her and, as she struggles, slams his hand into her lens.

The threat of violence in the United States made me all the more alert to the threat of real harm these people are facing. In one scene, when a soldier throws a man face down in a rocky field and kneels on his back as he cries “You’re hurting me,” I thought of George Floyd and saw some sort of equivalency between the experience of Black people here and Palestinians there. In this case, the soldier eventually drags the man to his feet and takes him away.

As the film’s director and editor, Tarabieh, who studied classical violin before turning to film, uses a single piece of music, George Friedrich Handel’s elegant and elegiac Sarabande in E minor, to suggest a tension between the moral chaos on screen and the possibility that a deeper order is at work here, a formal, ritualized saraband that, unlike the music we are hearing, denies the humanity of its dancers.

The film explores the many ways that Palestinians resist. Given the possibility of violence against them, it’s striking how actively they defend themselves, refusing to be intimidated. Mothers shout as young soldiers. Men argue and cajole, often invoking the possibility of rationality and order: “Where is your officer?” “Show me a court order and I will take down my flag.” In this film, language matters; It illuminates the delicate mechanics of occupation. To assert their dominance, soldiers address Palestinians in Hebrew. To assert their legitimacy, Palestinians speak to the soldiers in Arabic. English is the language of neutrality. When one speaks the other’s language, there’s a gesture of compromise, a show of respect, or an acknowledgement that the other simply may not speak one’s own language. The subtitles don’t always make these distinctions clear.

B’Tselem, the secular human rights organization that produced this film, takes its name from a Hebrew phrase in Genesis describing the creation of Adam as “B’tselem Elohim” – “in God’s image” – an injunction, perhaps, as to how we are to regard each other. In the context of this movie, the act of filming is an act of resistance to dehumanization. The idea that bearing witness is an act of resistance is deeply embedded in Jewish consciousness. It produced some of the greatest Holocaust literature committed to recording with precision and authenticity the details of daily life – Ann Frank and Emmanuel Ringenblum come to mind – in the belief that eventually, somewhere, other human beings would listen.

The Palestinian videographers seem to share this belief. The camera is their weapon of choice. Sometimes they use it actively as an extension of their own bodies, an assertion of their right to defend themselves and those near them. Sometimes they use it as a secret weapon, a way to spy on soldiers who don’t know they’re being watched. Sometimes they use it as a last resort, as when a woman alone in her house at night in Hebron records the shadowy figures on the street below who shout sexual insults and death threats, blare music and shine bright lights into her windows in order to force her to move out. The material she films is her act of defiance. At one point, when a soldier says to a Palestinian videographer, “Be careful. I have a gun,” he answers, “But I have a camera.”

Of Land and Bread builds toward the assertion that the camera is as powerful as the gun. Ehab Tarabieh ends the film with a long scene called “Bedtime Story” in which a father records a late-night intrusion into his home by a group of soldiers who seem to be on some sort of a training exercise; the soldier in charge tells the others, “keep both hands on your gun.” This soldier demands that the father awaken his four sleeping children to be questioned. He films as he wakes them, saying “Don’t be scared, I’m here.” But the children, barely awake, are scared, and after the soldiers go, each one asks their father, “Daddy, why did they come?” He answers, “They just came to visit us.” Then, as the boys are going back to sleep, the little girl, not ready yet to sleep, tells a long story – the bedtime story we’ve been waiting for – of an earlier incursion when the father was not at home and the soldiers broke down her mother’s bedroom door. The father’s voice contains many kinds of alarm as he asks, “Were you scared?” No, she answers – but she was afraid that the soldiers would take away her brother. And then, in a moment that says everything about the restorative power of controlling one’s own narrative, she says to her father, “Daddy, show me what you filmed.”

In my opinion, the film could have ended there instead of with the more highly constructed and therefore less powerful epilogue. In any case, the end credits are worth watching simply because they offer another vision of a life that could be possible; the names that scroll across the screen give credit to each of the Palestinians who did the filming and each of the Israelis who helped Tarabieh and B’Tselem turn ten years of material into a masterful film that brings us face to face with the Occupation.

The Camera Project is ongoing, and anyone can see the individual videos on the B’Tselem video channel dedicated to it. A Palestinian acquaintance of mine has watched them there.