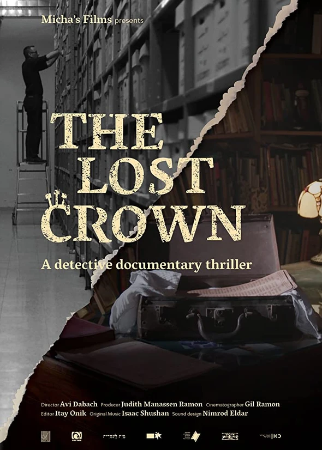

The Lost Crown 2019

Distributed by Collective Eye Films, 1315 SE 20th Ave. #3, Portland OR 97214; 971-236-2056

Produced by Judith Manassen Ramon

Directed by Avi Dabach

Streaming, 60 mins

College - General Adult

Immigration: Middle East; Judaism

Date Entered: 08/17/2020

Reviewed by Michal Goldman, Documentary Filmmaker; Member-Owner, New Day Films (https://www.newday.com/filmmaker/175)The Lost Crown is a film about a book, what people saw in it, what they made of it, its centrality to the communal and national identity of those who laid claim to it.

The book is the Aleppo Codex, known as The Crown. It was written around 930 CE in Tiberias by famous scribes, the Ben Asher family, who intended to set down for the first time a formal and final version of the Hebrew Bible. According to the great 12th century scholar and sage Moses Maimonides, it was the most accurate text of the Hebrew Bible in existence.

The Crown, like the people for whom it was written, has wandered. From Tiberias to Jerusalem, which the Crusaders laid waste in 1099 CE, taking The Crown with them. Then to the Jewish community of Fustat, in Egypt, which had ransomed it from the Crusaders; Jewish law dictates that Jews must redeem any Jew taken into slavery, and this text would have been considered a living being. It was there in Fustat that Maimonides made use of it while writing his great work, the Mishneh Torah. In the 14th century, Maimonides great-great-great-grandson migrated to Aleppo, then a prosperous commercial center, bringing The Crown with him. Aleppo’s Jews came to believe that it protected them, and in return, they protected it. For the next 600 years the codex remained there, clad in silver wrappings, locked in a safe in a small crypt dug into the rock below Aleppo’s Great Synagogue. Those who were permitted to read from it speak of the awe and terror they felt in its presence. In 1935, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a secular Zionist who would later become the second President of Israel, made a pilgrimage to Aleppo to see it: the rabbis of the Great Synagogue only allowed him to see its outer casing.

The Lost Crown focuses on what happened next, when the book left Aleppo and returned to Jerusalem, where, under circumstances that remain genuinely unknown or are, perhaps, government secrets, the Aleppo Codex was robbed of nearly 40% of its pages, including most of the Torah section. The film’s director, Avi Dabach, an Israeli of Syrian descent, tells the story in the first person, as though it had great personal relevance to him. And indeed, his great grandfather was “one of the guardians of The Crown when it was kept in the Great Synagogue of Aleppo.” He constructs the story as a mystery that he is determined to solve, creating for himself the on-screen persona of a somewhat bumbling would-be Syrian-Israeli Sherlock Holmes who has a coughing fit when he tries to smoke his pipe. But these narrative maneuvers turn out to be somewhat labored techniques that allow Dabach to stitch together a complicated story with many parts. The story is elegantly filmed, with lively interviews and vivid archival images, but it’s the spoken word, not the images, that drive this film forward.

Slowly, the real question emerges: How do a group of people deliberately and rapidly invent for themselves a national identity, trying to achieve in a matter of decades what for most nations is a multi-generational project unfolding over the course of several centuries? To some degree, this problem confronted all the newly-minted post-colonial nation-states of the 20th century, but nowhere was it more urgent or obvious than in Israel, where, in 1948, the United Nations recognized the national status of what was in fact a multi-national population still early in the process of migrating to the territory granted to it. In that situation, a meta-narrative justifying and validating the assertion of nationhood was crucial to the project’s success. Imagine the problem: all these people arrive in Palestine, soon to become Israel, telling their various origin stories in different languages; a perilous situation; the Bible tells us that Babel won’t survive. How then are all these immigrants to become convinced that something binds them together? That “something” had to be their Judaism and the language in which it was cast, though that, too, meant something quite different depending on where they came from, whether they were secular, socialist immigrants from Poland or America, or devoutly religious immigrants from Syria or Yemen.

When the secular, Eastern European Itzhak Ben-Zvi made his pilgrimage to Aleppo to see The Crown in 1935, its keepers didn’t consider him worthy of it, so they showed him only its outer covering. But soon the situation would be reversed. In 1947, after the United Nations partitioned Palestine, the Muslims of Aleppo rioted against the Jewish community, killing some of its residents and burning its Great Synagogue. The rumor spread that The Crown had been destroyed in the fire, and the Jewish community, realizing that the Aleppo Codex, an object of great monetary and spiritual value, was now vulnerable, let the rumor stand. In fact, though, the Synagogue’s sexton and his son had returned unseen to the ruins and rescued the book from the ashes, managing to find all but a few of the scattered pages. The film doesn’t give much context for these events: among the great upheavals that shook the Middle East over the next decades, the 1956 Suez War isn’t mentioned, nor, really, the increasing role of the Soviet Union in Syria. Instead the film follows the dispersion of the Syrian Jewish community to New York, Europe, and Israel as if these events happened in isolation, only in the context of Arab anti-Semitism.

In Israel, the secular, Eastern European Jews, whom the Syrian Jews regarded with scorn, were in control. They, not the Jews from the Middle East, defined the priorities of the new nation, establishing its first narrative and collecting the physical symbols that would support its claim to statehood. Archeology that buttressed the Biblical narrative was crucial, as were ancient Hebrew texts, no longer because of their continuing religious significance, but because they made visible the long-standing existence of something called the Jewish People.

In 1952, Itzhak Ben-Zvi became the second President of Israel, and he wanted The Crown more than any other object. He tried and failed to get the Aleppo community to give it up. But in 1957, recognizing the increasing fragility of their community, its leaders decided that they could no longer be confident of their ability to protect the book that was their spiritual heart, and they decided to smuggle it out of Syria and back to Jerusalem. They intended to place it in the hands of the Rabbi who was the head of the Syrian Jewish community there, and he was ready to receive it.

But it escaped him. In Israel, the European Jews regarded the Jews from the Arab lands as primitives. This prejudice justified their determination that manuscripts as ancient and valuable as The Crown must not remain in the hands of these Jews, where, as the film points out, they had remained safe for hundreds of years. Instead, after many fabulous twists and turns, The Crown, which at one point had been wrapped in cheesecloth and hidden in a washing machine under a sack of onions, reached Jerusalem, where the Israeli Secret Police awaited it: it was delivered into the possession of the Ben-Zvi Institute for the study of Jews from Arab lands. When it was next examined by independent scholars, nearly 200 pages, including the books of Genesis and Exodus, had gone missing. And this kind of thievery from the archives was not unusual.

The question remains: to whom does The Crown rightfully belong? Very close to the film’s end, Professor Eyal Ginio, the director of the Ben-Zvi Institute, answers: “It doesn’t belong to any particular community. It belongs to the people of Israel – the Jewish People.” Are they really one and the same? Avi Dobosch, the film’s director, doesn’t seem to think so; he gives himself the last word: “I believe that recognition of the cultural appropriation may open the way for the pages’ return.”

That statement too feels like a device. What matters more is that Dobosch tells the story of the State’s attitude toward its Arab-speaking immigrants calmly, without the rancor that a member of his parent’s generation might have deployed. By now it’s a familiar story, and Dobosch is looking for nuance, and possibly even for healing, in an era as dangerously divisive as any before it.

Awards:

2019 Miami Jewish Film Festival; 2019 New York Sephardic Jewish Film Festival; 2019 Boston Jewish Film Festival; 2019 UK Jewish Film Festival