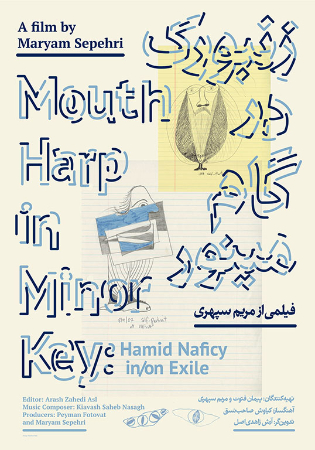

Mouth Harp in Minor Key: Hamid Naficy In/On Exile 2017

Distributed by Third World Newsreel, 545 Eighth Avenue, Suite 550, New York, NY 10018; 212-947-9277

Produced by Vinton Cerf

Directed by Maryam Sepehri

Streaming, 61 mins

College - General Adult

Immigration; Middle East Studies; Multiculturalism

Date Entered: 12/07/2020

Reviewed by Michal Goldman, Documentary Filmmaker; Member-Owner, New Day Films (https://www.newday.com/filmmaker/175)“Exile is a process of becoming…”

-- Hamid Naficy

Mouth Harp in Minor Key is a documentary by the Iranian-American filmmaker Maryam Sepehri about the Iranian scholar Hamid Naficy, whose studies have focused on two major themes – exile and Iranian Cinema – while living, writing and teaching in the United States.

The quote above comes from Naficy’s book, The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian Television in Los Angeles (1993), and it is central to the film. He reads a fuller version near the film’s end:

“Exile is a process of becoming, involving separation from home, a period of liminality and in-betweenness that can be temporary or permanent, and finally, incorporation into the dominant host country. Although separation begins with departure from the homeland, the imprint, the influence of home continues well into the remaining phases.”

A distinguished intellectual, Hamid Naficy comes from a family of distinguished Iranian intellectuals and public servants. A relative from his grandparents’ generation, Said Nafisi (1895-1966), was a noted historian, scholar of literature, poet and translator, co-founder in 1943 of the Iranian Society for Cultural Relations with the USSR; another relative, Moadeb Naficy, was guardian and doctor to Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran; a contemporary of Hamid’s is the author Azar Nafisi, who also lives in the U.S. and is best known for her memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran.

The film doesn’t mention any of these connections: instead, it focuses on Naficy’s own thoughts and, perhaps, his inner life. It begins with a short sequence of black and white images, formally composed and deliberately shot, that evokes a dream of Naficy’s that he associates with his exile from Iran. The film then changes style and location, bringing us into Naficy’s classroom at Midwestern University, where he has taught for a long time.

A younger filmmaker who began to make films while studying at Tehran Art University, Maryam Sepehri clearly admires Hamid Naficy’s work. She organizes her film according to the phases outlined in his statement quoted above: first, a section relating to his exile from Iran and his memories of childhood there, many of them suffused quite deliberately with nostalgia. Next, a discussion and evocation of the initial “liminality” resulting from exile and Naficy’s sense of displacement. These two sections, with their frequent quotes from Naficy’s work, play out over images sometimes of Iran, and sometimes of his daily life in the Midwest, where he often speaks in Farsi, as if to suggest that it doesn’t really matter where he actually is: his mind lives in the in-between. Perhaps because of the filmmaker’s commitment to Naficy’s description of the phases of exile, with integration into the host culture occurring at the end of the process, she doesn’t introduce Naficy’s happy domestic life with his wife and grown children until the last third of the film, so that for the first two thirds of it, I experienced Naficy as a man strangely in exile in his own fine and mysteriously homey house, wandering from room to room without another soul in sight.

The filmmaker observes her characters with respect, but she doesn’t draw close to them, nor does she draw far enough back to set them in context. And so, for one who doesn’t bring to this movie an already-deep understanding of the culture and recent history of Iran, the story feels a bit like a jewel without a setting. Although we hear a lot of Farsi, I’m left with the sense that some version of this story could have happened in so many other places. Maybe that’s what the filmmaker intended: for this to be about exile more generally.

Hamid Naficy is a theorist about culture and its displacement through exile. As he says in the film, “my theories come from below, from my own experiences.” His reflections are self-reflections.

And so, a psychological portrait begins to emerge of a man who sees himself, whether out of necessity or by choice, in contrast to his brother. He, Hamid, is the brother who will wander; his mother says, “My son will leave and not return.” And indeed, he does, coming to the US in 1964 and getting a BA in Telecommunications from the University of Southern California, then moving to UCLA for his MA in Theater Studies and his Ph.D. in Critical Studies in Film and Television. Meanwhile, his brother Saeed stays in Iran, where he becomes an activist and in the 1970s is arrested and executed by SAVAK, the Shah’s secret police. Although Hamid returns for brief periods to Iran, the Islamic Revolution of 1979 confirms his decision to make his home in the United States; he chooses exile, it isn’t forced upon him. In Iran, their mother has lost two sons, each differently. And though the surviving son could not have saved his brother, his exile seems at least in part a kind of penance, a deliberate self-banishment. In the film, he says, “Separation from you is in fact a series of separations…. Separation from mother, the mother and model of all separations.”

Saeed becomes the presence/absence that allows Hamid’s thought to fold in on itself, to consider itself more clearly in contrast to his brother’s reflection. He says, “From an aesthetic point of view, there’s a kind of pleasure in loss.”

The Iranian Government has never revealed to the family where Saeed is buried. And so, the earth of his home country takes on another layer of meaning. On a trip back to Iran, he says, “One day we went to a mine where they had cores samples which were cut into pieces. They gave me this piece and I brought it with me to America. It is earth from Iran – my homeland. You know the books about “exiled romantics” who take some of the dirt of their country with them. This is my romanticism.”

For Naficy, the dialogue on the part of the one who is present with the one who is absent sharpens his powers of self-observation, the way a moment of evanescence – a gleam of sunlight along the edge of a roof, a first afternoon shadow across the living room carpet – heightens one’s awareness of subtle shifts in objects and states of being one had considered immutable, or barely considered at all.

Naficy’s inner dialogue with his brother allows him to wipe away the boundary between past and present so that they coexist in him. In what for me is the most poignant and memorable scene of the film, Hamid’s memory of his brother Saeed’s death is triggered when he attends the funeral of a Jewish friend, Kitty, who has died of cancer. As he goes through the Jewish ritual of pouring a shovel-full of earth onto Kitty’s grave, he begins to cry, and he realizes that he’s crying for his brother, whose grave he cannot visit. Over beautiful, contemplative images of the monuments in a Christian cemetery on an autumn day, he says, “I knew then that my mourning and weeping that day stemmed from a tripartite sense of loss: that of Kitty to cancer, of Saeed to the firing squad, and of my country to exile.” He remembers that Kitty’s six-year-old daughter refused to pour dirt on her mother’s grave. “Clearly, she was not finished with her mother. Why should she bury her? Like I, who was not finished with my brother until then.”

The last third of the film explores Naficy’s involvement with and study of Iranian Cinema and the production of his magnum opus, the four-volume A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Now a new dialogue emerges, this time between Naficy, in his self-imposed exile, and the great Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, who stayed in Iran into, during, and after the Islamic Revolution. I must say that for me as a young filmmaker, Abbas Kiarostami’s films were a revelation when I finally got a chance to see them; they blew my mind. I had no idea you could make films like that, so lovingly attentive to the humblest details of human interaction, so quietly reflective of the spaces in which these moments occur, and just when I least expected it, so slyly and self-deprecatingly self-reflexive of the whole filmmaking process. Mouth Harp in a Minor Key makes me realize that I have Naficy to thank for my ongoing discovery of what has become one of my favorite world cinemas.

Naficy and Kiarostami share a slightly self-deprecating sense of humor. Walking over the graffiti-covered rocks along the shore of Lake Michigan, Naficy says, “Suddenly I’m profoundly struck by the seemingly mundane thought that life does indeed go on in the homeland without me.” A few years after the Islamic Revolution, Naficy brings Kiarostami to Los Angeles for a controversial festival of Iranian Cinema that some local Iranians boycott because it doesn’t condemn the Islamic Republic. In the theatre lobby, Kiarostami goes up to one of the demonstrators and offers to hold his placard for him so that the demonstrator can go inside and watch the films and then decide whether they should be boycotted or not.

In contrast to Kiarostami, Naficy says of himself, “I became more Iranian while being out of Iran.” The film’s final image evokes his liminality most powerfully: in a static, black-and-white shot, we see the back of Naficy’s head in the foreground; he is facing away from us, standing very still at the edge of a large space, watching people who are watching others. He thinks that exile is sometimes a choice people make; it sharpens their awareness and memory of “home.”

On the other hand, he sees that the choice to stay also can bear fruit. In an interview about Kiarostami after his death that is not part of this film, Naficy says: “There was something in the earth and culture and society of Iran that kept him alive, and I think his films are very filled, fecund with Iranian sensibilities. He is both the most international, the most global filmmaker from Iran, and also the most local.” (Interview with Iranian film scholar Hamid Naficy, “Taste of Cherry” [1997] by Abbas Kiarostami, from the Criterion Collection)

The same root, another route.

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.