Henry Glassie: Field Work 2019

Distributed by Grasshopper Film, 12 East 32nd St., 4th Floor, New York, NY 10016

Produced by Tina O'Reilly

Directed by Pat Collins

Streaming, 105 mins

College - General Adult

Art; Biography; Folklore

Date Entered: 03/24/2021

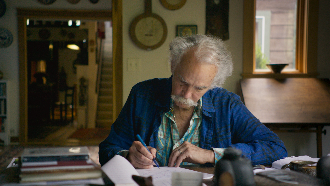

Reviewed by Patrick Crowley, Metadata Librarian for Cataloging and Digital Projects, Southern Connecticut State UniversityHenry Glassie: Field Work is a beautiful, meandering, and visually-rich documentary whose emergent narrative structure vividly captures the character, philosophy, and career of its primary subject, the noted folklorist Henry Glassie, while also beautifully integrating images, video, and sounds of the cultural production of Glassie’s subjects over the years.

The structure of the film meanders like a river through Glassie’s long career investigating folk art traditions across the United States and the world. It bypasses chronology as an organizing principle and eschews the normal tropes of biographical documentary.

Glassie’s voice opens the film, but his presence is firmly in the background for the first 40 minutes of the film, the lens instead focusing on the Brazilian folk artists whom Glassie’s recent work treats. An early lack of narration asks the viewer to focus solely on the artist and the art as it is being enacted. And, as personal narratives of the artists begin to be overlaid on the film, the viewers begin to layer images of the art and method with personal philosophies of the artists that are at once culturally informed and individually expressed. It is only when we begin to see Glassie in frame, attentively watching the same artists, that we realize we have been watching these artists as Glassie does. And we are now watching Glassie as Glassie watches these artists, on his own terms and as an exemplar of a type of scholarly art. And, as we move into the rest of the film, Glassie’s voice replaces those of the artists, articulating a philosophy of research method that informs his life’s work.

The structure of the film is decidedly obtuse to begin with. It takes some time to realize the framework that the filmmakers are building. Once apparent, it could be said that the structure of the film is an application of Glassie’s own anthropologically-centered folklore research method to Glassie himself—an evocatively filmed musing on Glassie’s inquiry into what beauty means in different cultures, on approaches to culture on its own terms, on the primacy of landscape over hard chronology in understanding cultural production and values, on the importance of individual people in understanding culture, and on finding in any given culture what it uniquely excels in by following what his interlocutors say. All of these precepts can be seen to play out in examining Glassie’s long and geographically diverse works.

The film crew documents Glassie’s most current work in Brazil and in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, but this film is not about these more recent projects, as much as it is about setting these among the varied projects Glassie pursued across the globe. Using new and archival film, images of Glassie’s notes and maps, and original audio of musical performances and oral histories collected by Glassie, the film documents his early-career work in the American South, in Western Anatolia, and in Ireland, where he embedded himself in a community for 10 years. Again, it is important to stress that these are not arranged in a chronological order, but rather follow a conversational flow guided by the voice and metaphysical musings of Glassie on his own work in the same way that the work began with Brazilian artists narrating their process, their inspirations, and the personal meaning of their work.

In thinking about what uses this documentary can have, it is worth noting the long, unnarrated passages showing the artistic process of folk artisans. Notable are clay and wood sculptors in the Brazil section and potters in the sections on North Carolina, the latter showing the loading and firing of a wood-fired, brick kiln. These are notable both from the anthropological point of view (i.e. they show shared, but distinct heritage of artistic methods) but also from the artistic point of view (i.e. showing in wonderfully filmed detail diverse methods of crafting in multiple media).

In evaluating this documentary for class use, it is fair to say that some disciplines will find it extremely useful in its entirely (e.g. folklore and cultural anthropology), especially in departments that use Glassie’s work. Other disciplines may find it useful for its careful documentation of crafting process (e.g. studio art departments). For such programs this is strongly recommended. I think that there is also an argument that it is worth studying from the perspective of a film program based on its own idiosyncratic and interesting approach to the documentary form. But it is worth noting that it is a sprawling film and focuses more on Glassie’s oral history of his career and work than it does on that work itself. As such, I see that it would have limited use outside of disciplines in which Glassie’s work is core. While a History or Latin American Studies Department might find excerpts of use for illustrating folk crafting in these areas, the question, especially as smaller institutions, will be whether the high, albeit one-time, price-tag will be justified. On balance, this film is recommended with reservations, those reservations being price, length, and wide applicability.

Awards:

Best Irish Documentary Award at Galway Film Fleadh; NTR De Kennis van Nu Audience Award at InScience Film Festival

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.