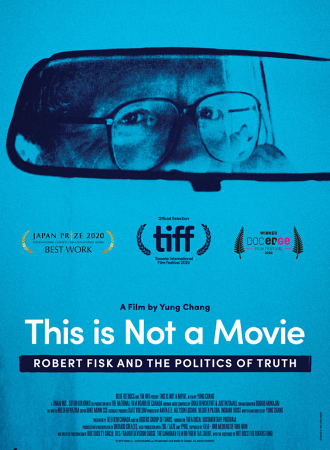

This Is Not a Movie 2019

Distributed by Kimstim, 417 13th Street #2,

Brooklyn, New York 11215

Produced by National Film Board of Canada

Directed by Yung Chang

Streaming, 106 mins

College - General Adult

Biography; History; Journalism

Date Entered: 05/26/2021

Reviewed by Catherine Michael, Communications & Legal Studies Librarian, Ithaca CollegeAs I watched this film in May of 2021, a film filled with discussions of the Middle East and how the media covers it, a new conflict began between Israel and Palestine. Once you watch the film, you become conscious of word choices such as conflict, clashes, fences, and terrorism, terms that can convey the wrong message to readers about the nature of the event. What do you call this event? What history shaped it? How is the story being told?

This is Not a Movie, a profile of esteemed foreign correspondent and historian, Dr. Robert Fisk, was released in 2019 (his doctoral degree was in political science). The last scene of the film displayed the conclusion about the final report (March, 2019) on the Douma attack in Syria (April, 2018). Later that year, on October 30, 2020, Fisk died. Thankfully, film captured his life, his journalistic practice, his wisdom from living and studying Middle Eastern history, and his philosophy. It is a treasure for having artfully and thoughtfully filmed this biographic documentary before his death. Director, Young Chang (Up the Yangtze, 2007), chose a worthy subject at a key window of time.

Fisk endured many criticisms throughout his career. His reporting on Douma was one of the final examples. After the Douma attack in Syria, he could not verify, after his boots-on-the-ground journalism, clear evidence of the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government. While he conceded that the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons might ultimately determine chemicals were used, he reported the unbiased facts as he found them after being provided access, with other reporters, to the scene of the crime. Criticism against him was that his reporting was used as propaganda by Russia and Syria. Yet that outcome was not in his control. His job as a journalist was to report what happened to those who suffered as he experienced it firsthand. In war reporting, there is pressure to report for the side of your government. In his life, Robert Fisk did not give into that pressure and focused on reporting the facts as he discovered them through interviews with those involved.

Given his education and expertise, Fisk has a developed and defined approach to journalistic practice conveyed by the documentary. Students of journalism should view the documentary to consider his advice. A lot of it is expressed in voiceovers and in the context of his life and work at the time of filming. The documentary opens in medias res at the Iraqi Frontline in 1980, we hear him utter, “Wonder why I go into journalism?” as he runs from the danger of battle, seeking the safety of his car. The film answers this question.

Working for The Times in Belfast, Northern Ireland prepared him for reporting in the Middle East. It is where he first realized that the British Army was not the primary source of information and its authority needed to be challenged. He left reporting for The Times of London to report for the The Independent. The Times, purchased by Murdoch, changed his report of how an American warship shot down an Iranian civilian aircraft; additionally, The Times ran a false editorial that suggested the pilot was on a suicide mission. The paper lost his trust.

The title of the film, This Is Not a Movie, refers to one of his aspirations to become a journalist. Alfred Hitchcock’s film, Foreign Correspondent (1940), presented a romantic vision full of adventures and intrigue. His other aspiration would be the military career of his father who, later in life, realized that the poppy was not a symbol of sacrifice but of lies from commanders to soldiers; the poppy inspired men to battle and was not in reality a symbol of peace and remembrance. His father, in a final act of courage, refused to partake in an execution party and was forced to leave the army; Fisk treasures this memory of his father’s disobedience; the film captures his pride for his father through his expression. His father also broke another rule: he brought a camera to the battle fields of World War I to record what he saw.

Throughout so many wars, over so many years, the one that appeared to affect him most deeply was bearing witness to the massacre in Sabra and Shatila in Beirut, Lebanon (1982). Footage and photos of the dead bodies are shown through his narration of the tragedy. These photos are a necessary part of the storytelling. Fisk returned to the scene in more recent years to convey how it contributed to the difficulties living in the camp today. The column he filed ensures the massacre is not forgotten. The filmmaker shifted to a scene where Fisk examines photographs of the Armenian genocide and discusses the importance of telling the stories of survivors. During Sabra and Shatila, Fisk was forced to crawl over bodies to safety. Despite this gruesome memory, he remained emotionally stoic when confronting violence; he explained that his mission was to record the stories of those who have suffered.

Another hallmark of his career were his interviews with Osama Bin Laden; he describes one of the meetings in the documentary. His reporting of 9/11 centered on why the tragedy happened. In contrast, most of the media focused on calling the event an act of terrorism without including or understanding the historical context. After the World Trade Center attack, we listen with Fisk to an audio clip of a fiery discussion with lawyer Alan Dershowitz; they both regarded one another as dangerous. Dershowitz accused Dr. Fisk of anti-Semitism and moral relativism. Fisk accused Dershowitz of shutting down the conversation by using a cheap and false slur and simplifying the event with the word terror. That scene then transitioned nicely into a presentation by Fisk where he elaborates upon the problem of the “desemantization of war” by using terms such as terror without explaining the background and causes of events.

In the Occupied West Bank, we overhear Fisk talking to two esteemed colleagues, Amria Hass, Israeli journalist for Haaretz, and Antony Loewenstein, a freelance journalist. Hass is highly regarded for her own integrity. Her parents survived the Holocaust and instilled the value of human rights in her. Like Fisk, if they challenge authority, they know they will be accused of being a traitor, or for Fisk, anti-Semitic. They both dismiss such criticisms in order to maintain their integrity. Amira explained that the truth is not about being fashionable, the truth relies on logic and analysis. Loewenstein discussed with Fisk the contemporary problem of misinformation on the internet. Fisk advises journalists against gathering news from social media and emphasized news gathering by being on the ground.

The film contains a variety of visual images including: historical photographs, old footage of Fisk in his early career, shots in his home writing his column amidst his vast collection of books and articles, first person camerawork of the frontline full of bombed out buildings, audio interviews, lectures, in conversation with colleagues, etc. I particularly enjoyed the presentation of Fisk’s collection of press passes; they visually convey the many places he’s been. There is a good balance between contemplative scenes of him writing and ride along shots in the field. Changes between segments, mainly focusing on a different area of the Middle East, have titles announcing the location. The various events are not chronologically arranged but are from various periods in time; I include them here as a Table of Contents: Iraqi Frontline 1980; Homs, Syria 2018; Mont Akrad, Northern Syria 2016; Belfast Northern Ireland –1972-75; Beirut Lebanon: Israeli Invasion of Lebanon 1982: Sabra & Shatila Refugee Camp; Armenian Museum of America, Boston; UN Blue Line, Lebanon -Israeli Border; Srednja Bosnia, Central Bosnia; Douma, Syria, April 7, 2018; Beirut, Lebanon; Occupied West Bank; Khan Al-Ahmar Village, West Bank. The presentation of these myriad locales follows the journalist’s memory; this enhanced the conversational feel to the documentary; as he speaks, a memory is demonstrated. It evokes an intimate sense that Fisk is talking to you as a friend and colleague.

In the more current segments, the filmmakers take us to Syria where we see him searching for the hyped battle in Idlib; he found little evidence of the battle while there and that became his headline. The final two segments contain contrasting interviews with Chaim Silberstein, a Beit El Israeli Settler, and Sulieman Khatib, a Palestinian whose land was taken from his family. Fisk has been on the beat so long, he reunites with Khatib to interview him again twenty-five years after his land was taken from him. The event leaves the correspondent pondering on the impact of his career. The viewer is left to contemplate the two voices (for more insight, you can also find his Independent columns based on the interviews by searching for the interviewee’s name with Fisk’s).

Fisk likened reporting to reading a great novelist like Tolstoy. There is always another chapter to read and, as an author of human history, he recorded each chapter of it. Telling that story is part of the reason why he went into journalism; the other was that he was a humanitarian. Not only is this film recommended as a biography of a life well lived, but as a testimony and presentation of war and its consequences. It is not Hitchcock’s feature, but a documentary of the tragedy of war and the idealism of a reporter who hopes, by recording that tragedy, there may come change. Watching this life of an intrepid foreign war correspondent, with all the risks of frontline reporting, we, too, bear witness to mankind’s cruelty, our ability to kill and destroy; it is certainly not a romantic movie. In Syria, he contemplated the capacity of humans to create war and destruction, to permit such tragedy. It is not easy to witness with Fisk the story of death, war, and massacre, but viewers must bear witness, learn the history and the context of that war, and use that information to stop future wars.

One way to instill trust in journalism is to understand all that goes into writing a story; that method is called transparency. Learning how Fisk left The Times for the Independent reveals his dedication to truth; understanding this dedication increases trust. He was a soldier for the truth and worth remembering. The film should inspire young journalists to follow his example of integrity, compassion and sacrifice, his method of telling the story of those who suffer, and his sensitivity to the words chosen to tell that story.

As I complete this review there has been a ceasefire thanks to mediation from Egypt and Qatar. All those who have seen this film will read contemporary news from the Middle East with sharper eyes and ears.

Awards:

Official Selection: Toronto International Film Festival, Toronto, Canada (2019); DOC NYC, New York, United States (2019); RIDM, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (2019); Palm Springs International Film Festival, Palm Springs, California, United States (2020). Best of Fests: Doc Edge Festival 2020, Wellington, New Zealand (2020). Best Work in the Lifelong Learning Division (The Governor of Tokyo Prize), Japan Prize International Educational Contest, Tokyo (2020)

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.