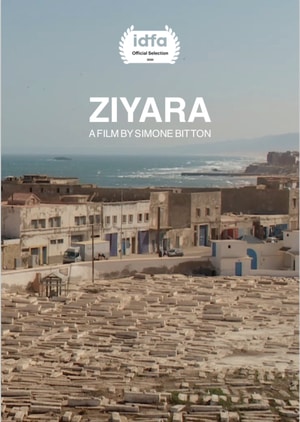

Ziyara 2020

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Thierry Lenouvel, Lamia Chraibi, and Olivier Dubois

Directed by Simone Bitton

Streaming, 99 mins

College - General Adult

Islamic Studies; Jewish Studies; Middle East Studies

Date Entered: 11/18/2021

Reviewed by Michal Goldman, Documentary Filmmaker; Member-Owner, New Day Films (https://www.newday.com/filmmaker/175)Ziyara is a tender, beautiful film that immerses the viewer in a sense of place. The filmmaker, Simone Bitton, grew up in Morocco until, when she was twelve, her family left it for France, becoming part of the exodus of a Jewish population present in Morocco since late antiquity and augmented by a series of in-migrations from the 14th century on. Beginning in the late 1940s after the creation of the state of Israel and accelerating in the 1960s through the late 1970s, the exodus of these Moroccans is by now nearly complete. Bitton has spoken of her own increasingly frequent visits to her birth country over the last decades; “Ziyara,” an Arabic word meaning “visit,” also suggests a pilgrimage.

One makes a pilgrimage in search of something; Bitton says Ziyara is her road movie, a story marked by a series encounters with places and people punctuated by shots of the open road. As in any road trip, we don’t learn anything outside of what happens within the encounters themselves. The film offers tantalizing details waiting to be explored: a public scribe whose shop was given to his father by its Jewish owner upon his departure; a dealer in fine antiques who says that these days it’s wealthy Gulf Arabs who buy the Jewish items.

Bitton visits the tombs of Jewish saints; as she puts it, while most of Morocco’s Jews have left, their saints have stayed behind. These places, as she films them, are quiet, remarkably peaceful, often beautiful, and with rare exceptions, strikingly empty of people. Her images convey a Jewish absence so palpable that it seems to have drained away most other people too. It’s hard not to compare this presence of absence to what visitors to Jewish sites in Poland experience. But this is different: though Morocco’s Jews left in response to mounting political and economic pressures and prejudice, they left freely in search of new lives.

Unlike a physical journey, the logic of geography isn’t what structures this story. Bitton is after something, and she builds her film to lead us to it. She wants to understand what Morocco is now, without its Jews. Toward that end, she avoids interviewing the Jews who remain, and she provides no historical context for the Jewish monuments she visits – saints’ tombs, cemeteries, synagogues. Instead, she focuses on the Muslim men and women who take care of these places with devotion and care, sometimes living in poverty in remote areas for a pittance paid by a largely absent Jewish population, sometimes inheriting their post from father or grandfather, often speaking of Jewish families who treated them with kindness. She always films the caretakers as inseparable from their sites, usually carrying a ring of keys that affirm that they are the ones who can let us in. And let us in they do.

They speak of the Jewish saints as part of an ancient faith that may predate monotheism and continues now alongside it. The film begins with Bitton lighting a candle at the tomb of Abram Moul Niss – Abram Master of Miracles - west of Casablanca. Most of these Jewish saints have names like Master of Miracles, Master of the Date Palm, Master of Water. Jews and Muslims alike come to them in search of healing and blessings that often seem to inhere in the site itself. Muslim and Jewish women seeking husbands and fertility bathe in the springs and rivers near these saints’ tombs. The primitive association of flowing water with life itself also permeates formal Judaism, which describes the Torah as an ever-flowing spring. When Bitton, filming inside a beautiful old synagogue in Fez, shows us its Mikveh – the women’s ritual bath always fed by a living stream – I realized that these ancient beliefs infuse Jewish monotheism, and perhaps they always have.

Bitton highlights the interconnections between Jews and Muslims and the complementary economy these connections produced. One man describes it this way: The Muslim, who cannot drink alcohol, sells the Jew his fermenting fruit: “In that way, nothing is wasted. The two cultures are complementary, and that’s what’s missed with the departure of the Jews.” The Shabbos goy is an old institution that acknowledges interdependence flowing from difference. The Muslim caretaker is what remains of it.

The tombs Bitton visits belong to men, except for one: that of a young woman who committed suicide rather than marry a man she didn’t want. Is this the tomb of the famous 19th century Jewish martyr, the beautiful Sol Hachuel, who preferred death to forced marriage to a non-Jew? The filmmaker doesn’t tell us; instead, she focuses on the person who shows us the grave, an entrancingly beautiful young Muslim girl who, mixing French and Arabic as many of these speakers do, gives us a glimpse of her own life, her day at school, her aspirations.

In the second half of the film, Bitton develops her thesis that in Morocco, it is Muslims who preserve the remnants of Jewish presence and, by implication, feel the effects of its absence. In one of the most extended scenes of the film, Zhor Rehihil, a clearly secular Muslim woman who is curator of the Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca – the only such museum in the Arab world –dresses a Torah in its ritual robes with the tenderness usually reserved for a living creature; wearing the white gloves emblematic of her profession, she admits that before she handles one of the Torahs in the museum’s collection she says “Bismillah” to herself, asking God’s permission to touch this sacred object and, perhaps, asking forgiveness. Bitton interviews Muslims who display deep knowledge of and respect for Jewish ritual practice. The elegant, dignified caretaker of a large synagogue in Meknes that still holds services for its twenty-eight remaining members proudly shows us its ten Torah scrolls. A woman who takes care of a Jewish cemetery has taught herself Hebrew to make the information on all the graves available to any visitor. Aomar Boum, Professor of Sephardic Studies at UCLA, has come to Essaouira to establish Bayt Dakira, a research center for the study of Arab Jewry: “The Jews will soon be gone. The Muslims are appropriating this history.”

Only near the end of the film does Bitton include an overt discussion of politics, for by now she has established that the political forces she’s interested in are the ones that unite Jew and Muslim rather than divide them. A black Moroccan, Amoar Boum approaches the study of Arab Jews through his own experience of Moroccan racism. In Essaouira’s Jewish cemetery, in an act of personal pilgrimage, Bitton visits the grave of Abraham Serfaty. Born in 1926, Serafty was a dissident and pro-democracy activist; Bitton calls him “the most famous Moroccan political prisoner of the twentieth century.” Sitting on Serfaty’s grave, the economist and activist Fouad Abdelmoumni, three decades his junior, speaks of the formative influence Serfaty had on him as a young Muslim beginning to struggle for democracy in Morocco: Serfaty renounced sectarianism. Abdelmoumni then makes the point toward which this film has been moving all along: “Moroccan Judaism can’t be considered external to us. It is part of our collective heritage. The hemorrhaging of the Jewish community is a wound in the Moroccan body. We have become impoverished in our diversity.”

The film’s final scene is a sort of coda, throwing into relief all we’ve seen up to this point: instead of a key opening a lock, we watch a hand smashing a lock with a hammer. When the door opens, instead of entering a site carefully kept, we enter a dark, trashed space. Our informant tells us with some embarrassment that this had been his town’s synagogue until, after all the Jews had left, it became the town’s first cinema. A Muslim teenager sitting on synagogue benches, he saw his first movie there– an Egyptian musical staring the famous Abdel Halim Hafez – followed by many others from Europe and America. Bitton, always a kind off-screen presence, tells him that, being a filmmaker, she’s happy to think of an empty synagogue becoming a cinema. He’s comforted. And she, without comment, lights a last candle in this darkness.

Because of its clear themes along with the cinematic interest of its filmmaking, Ziyara invites discussion and engagement across a range of subjects. Because the filmmaker is committed to showing us only what she herself encounters, those who use this film may want to provide the background and context that the film itself avoids. The film is compelling; the results in the classroom should be worth the extra work.

Awards: Cinéma du Réel 2021; Middle East Studies Association (MESA) FilmFest 2021; Amsterdam International Documentary Film Festival 2020; Cairo International Film Festival 2020

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.