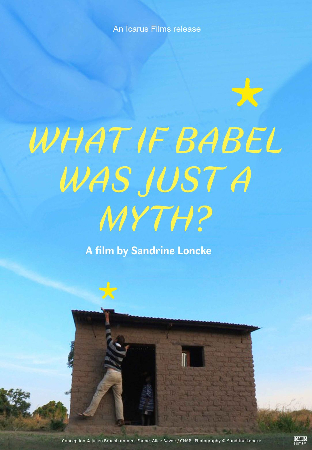

What If Babel Was Just a Myth? 2019

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Sandrine Loncke

Directed by Sandrine Loncke

Streaming, 56 mins

High School - General Adult

Anthropology; Linguistics

Date Entered: 12/13/2021

Reviewed by Patrick Crowley, Metadata Librarian for Cataloging and Digital Projects, Southern Connecticut State UniversityWhat if Babel were a Myth?, a film by ethnomusicologist Sandrine Loncke, presents viewers with two overarching philosophical questions in its first few minutes. Is it a problem that the world is looking at a 60% reduction in language diversity, particularly among minority-spoken languages, by the end of the century? And, if we accept that languages die out, why is it important to document and preserve them? The film very clearly and directly answers these questions in the narrating voices of Sandrine Loncke and Florian Lionnet, who initiated the project to document the Láàl language spoken by only 700 people in two villages in Chad. Lionnet and Locke use the Gori People and Láàl as a case study to argue for the complex ways in which different languages and, by extension, music and songs, illustrate a group’s history, cultural priorities, and world view. Loss of a language means losing a perspective on life and indeed a perspective on history. In the case of Láàl, a language isolate among other more-related languages, its survival may give insight into migration patterns and language formation. Language and music also document a way of life for a people and the way that they interact with the world. Relative vocabulary richness or paucity can show cultural priority, while music and operates as a punctuation for shared group bonding and work. Narration is accompanied by animated linking videos that illustrate linguistic points in an accessible and poignant way. Notable is the vivid geographic animation that shows the stark isolation of Láàl among other language groups.

Narration and animation act as framework which surround three types of video: firstly, fly-on-the-wall documentation of the Gori people speaking, working, singing, and dancing, the kinds of material that form the core evidence of the ethnological and linguistic work that Loncke, Lionnet, and ethnologist Remady Hoïnathy are setting out to do; secondly, video taken of researchers working with village inhabitants, compiling dictionaries, walking the fields and learning vocabulary, and discussing storytelling and village history; and finally, direct interviews with members of the village and its diaspora in the city. What links all of these is the question of language. We see its collection and documentation; its multiplicity as researchers work with villagers who slip easily between Láàl, French, Arabic, and other local languages; its use in celebratory and work song; and we begin to learn not just about Láàl, but about how the Gori people conceive of language, language acquisition, and language preservation.

The final form of video is perhaps the most eloquent in direct service of the film’s theme, as villagers discuss their own relationship to their language and the various other languages that they have learned as they interact or intermarry with neighboring peoples and language groups. The picture that emerges from these interviews is one of a radically polyglot context, where an individual often knows up to six languages, and, crucially, values that lifestyle. Poignant stories include wives from other villages who have come to Gori and learned Láàl or the household of Gori descendants living in the more distant city of Sarh, who maintain Láàl in their household, essentially preserving their language as a marker of their unique culture.

If there is a criticism to be made of the film, it is that the variety of types of footage do not always flow as easily as one would hope. The film slips between documentation of the project and documentation of the people; between watching the people and watching the researchers watching the people; and, tonally, between the wider question of language diversity and Láàl as a case study. The film is framed by the arrival and departure of the researchers, delineating a research season. The strong focus on documentation methods and technology balanced with minimally mediated footage of people in their daily lives creates some sharp transitions that even the well-conceived and deployed linking animations do not fully smooth over.

This documentary is Recommended with Reservations. For an institution with a strong Anthropology, Linguistics, Ethnography, or African Studies program, this would be an invaluable addition to a collection. Beyond that, I feel that it would be of more limited value. At smaller institutions, it might be a worthwhile investment for precisely some of the reasons this reviewer found it disjointed. In other words, the very fact that it is once a document of the process of ethnography as it is an ethnographic documentation might grant it multiple use-cases in one item.

Awards: Grand Prize, International Festival of Ethnological Film of Belgrad; Best Scientific Documentary Award, Pärnu Film Festival; Finalist Best University Film, LabMeCrazy Science Film Festival of Pamplona; Finalist Best Documentary, Rome Prisma Independent Film Awards; Audience Award, Festival International du film chamanique de Sarlat; Merit Award, Awareness Film Festival of Los Angeles

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.