Antisemitism 2020

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Paul Cadieux, Céline Nusse, Maryse Rouillard, Paul Rozenberg, and Ilan Ziv

Directed by Ilan Ziv

Streaming, 120 mins

College - General Adult

Arab-Israeli Conflict; Human Rights; Jewish Studies; Race Relations

Date Entered: 04/19/2022

Reviewed by Michal Goldman, Documentary Filmmaker; Member-Owner, New Day Films (https://www.newday.com/filmmaker/175)From its opening moments, this elegant film makes us feel that we are in good hands as it explores its difficult, painful theme. Over surprisingly beautiful aerial footage from 1945 of Berlin in ruins, the narrator asks the motivating question: Why and how did antisemitism survive Hitler’s defeat? The question allows filmmaker Ilan Ziv to cast his film as a mystery and bring us along as he searches for the clues that will solve it. His persistent attention and the sophistication of his filmmaking allow us to stay engaged over the next two hours, eager for the next clue, the next revelation, even as he offers us an encapsulated history of antisemitism in all its perversity. Because he doesn’t turn away, we don’t either.

Ziv situates his exploration primarily in France. He interweaves three stories that intersect in Paris and branch out to at least touch on the rest of Europe, the United States, Russia, and the Middle East. The Dreyfus affair leads us back to the roots of anti-Judaism in the Middle Ages, and forward to the internal contradictions within the French Revolution, the Republic, and liberalism itself that make room for antisemitism’s repeated resurgence. Antisemitism, we are reminded, has evolved from the basic human need to construct an “other” to explain the challenges we face in the world, a need that gains urgency during periods of rapid change and resulting displacement. Since the Middle Ages in Europe, this “other” has worn a mask named The Jew, a mask linked to certain problematic and recurrent forces: money, conspiracy, the will to power. The film asserts that the trial and conviction of Alfred Dreyfus for treason on the basis of trumped-up evidence marked the first time that these antisemitic tropes were embraced and deployed by the State.

The second story is that of Theodore Herzl, who as a young journalist was present at the formal ceremony in the Paris Military Academy courtyard that degraded Dreyfus in public while a crowd outside the gates shouted its hatred of him. This reviewer was struck by the way the trappings of statehood legitimize and bestow dignity on proceedings that, in the case of Dreyfus, were actually a sham. Through Herzl, the film explores “a cruel irony of history:” how the creation of a Jewish state in the Middle East imported antisemitism into that region and fueled a resurgence of it in Europe.

Through Dreyfus and Herzl, we encounter figures like the German polemicist Wilhelm Marr, who saw Jews as a “foreign body” within the emerging German polity, and who coined the term “antisemitism” as a stance worthy of praise. In France, Edouard Drumont became antisemitism’s “guru.” The film places these developments in the wider historical context of post-1870s Europe, a period of tumultuous change. Marr was the first to define Jews as a race, a definition that, in his mind and Drumont’s, led inexorably to the conclusion that Germany and France were already engaged in a race war for their own survival. It’s not a big step from here to Hitler.

The film interweaves a third, less famous but more contemporary story with the other two: that of the French Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll, murdered at the age of 85 in 2018 in her apartment by two men who robbed her, stabbed her 11 times, and then set multiple fires in her rooms. One of these men was the son of an immigrant Arab neighbor whom she knew well. The film uses this story to bring all the historical forces and racist tropes outlined in the film into the present, and finally, to explore the depths of rage expressed in this murder and others like it. Her story, along with Herzl’s, allows the filmmaker to examine the rise of anti-Zionism after the 1967 war and especially with the invasion of Lebanon and the massacres of Sabra and Shatila, events that led to disillusionment within and outside Israel with state policy and even with the state itself.

The film touches on the perverse effects of French colonialism on the Jewish residents of Algeria, an important aspect of a story more or less repeated by other European colonial or imperialist powers, like the British in Egypt. If I have any issue with this splendid film, it’s in this area: it seems to me that the contradictions between the humanist ideals of European democracies as expressed at home and their imperial ambitions abroad may have something to tell us about the repeated resurgence of antisemitism and could have been more fully explored. As an American Jew, I also found myself wondering to what extent this persistent “othering” is internalized by Jews themselves.

Most viewers, and most students, will learn a great deal from this film. The cinematography, archival materials, and animation engage us. The thoughtful and thought-provoking narration, beautifully delivered by Rachida Brakni, challenges us. The experts interviewed cover a wide range of disciplines and speak with quiet urgency. The beautiful original music by Robert Marcel LePage deserves special mention.

All this brings us to the film’s final conclusion: that antisemitism is with us to stay because it arises from the toxic fusion of political ambitions with individual psychological needs we aren’t likely to eradicate. The psychiatric expert Michel Debec, who has testified at major trials for antisemitic crimes, tells us that antisemitism is “indispensable” because through it, the individual finds his or her identity. The rage expressed in these violent crimes comes from the need to prove that one is, indeed, a true anti-Semite, capable of “doing what needs to be done.”

Many, but by no means all, French people stand against this perpetuation of race war and with those who are targeted by it. The film gives the last word to two women from marginalized and threatened groups, in whom, maybe not so surprisingly, the deep humanistic values of the French Republic find their clearest voice. Latifa Ibn Ziaten, a Muslim woman whose son was mistakenly murdered as a Jew, has taken it as her mission to speak out on behalf of the value of each life in spite of lack of communal support and the death threats she receives. Faced with the need for an armed guard at the entrance to her synagogue at all times, Delphine Horvilleur, Rabbi and essayist, ends the film with the questions she believes all French citizens should be united in asking: "What can we do to keep all our children safe? What can we do to keep this ship of France from sinking?"

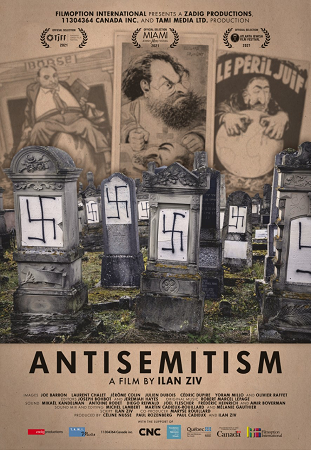

Awards: Toronto Jewish Film Festival; Atlanta Jewish Film Festival; Miami Jewish Film Festival; Silicon Valley Jewish Film Festival

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.