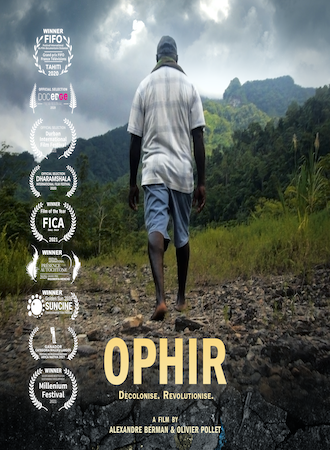

Ophir 2020

Distributed by Documentary Educational Resources, 108 Water Street, 5A, Watertown, MA 02472; 617-926-0491

Produced by Illan Girard, Olivier Pollet, and Kristan Lasslett

Directed by Alexandre Berman and Olivier Pollet

Streaming, 97 mins

College - General Adult

Environmentalism; Human Rights; Native Peoples

Date Entered: 01/05/2023

Reviewed by Abbey B. Lewis, STEM Learning & Collections Librarian, University of Colorado BoulderWithin the first few minutes of Ophir a man explains why that name is no longer used, “Captain Bougainville came and put his name on top of this name.” He’s referring to an event that happened over three hundred years ago, the beginning of the environmental and human exploitation that has played a central role in the island’s history ever since. The film focuses on more recent events related to Bougainville Copper Limited’s establishment of the Panguna Mine which led to devastating environmental impacts, setting off a civil war and Bougainvillians’ ongoing pursuit for independence.

Ophir follows a complicated, but familiar story of colonialism with its abuses of people and natural resources. The main narrative is told solely by Bougainvillians themselves as they speak in community meetings or directly to the camera, detailing heartbreaking stories of dead or missing loved ones and the complex political obstacles that stand in the way of their freedom. These first-hand, contemporary accounts of the lasting impacts of colonialism form the core of the film. A second, more sinister narrative is told through old films about Bougainville Copper Limited and the text of a consultants’ report to the company which explains how the psychological mechanisms of colonialism work. In the report, Bougainville Copper Limited is advised on the importance of education, which can be used for indoctrination and propaganda, and material goods, which can cement Bouganvillians’ dependence on the company. There’s an eerie parallel in the primary narrative as Bouganvillians’ describe these same tactics, seeing them for what they are.

The emphasis of this film is on people, rather than the environment, making some of the filmmakers’ choices seem somewhat strange. We are rarely given much information about the speakers themselves. Only a few names are provided, and this inclusion seems almost haphazard as these are mostly given when speakers introduce themselves or address one another in public meetings. Some individuals seem to fulfill important roles in their communities, appearing multiple times, but this needs to be inferred, as the film makes no effort to explain what those roles might be.

There’s much to learn from Ophir, but instructors should be mindful that because the film is scant on any details that don’t come directly from Bougainvillians or the mining company, students may need more introduction to Bougainville’s history and current state. Although most of the film is in English, significant and important parts are spoken in Tok Pisin and Nasioi, making the translated subtitles necessary. Ophir would be a good addition to collections at universities with strong Ethnic Studies programs, particularly those that explore indigeneity and international contexts. Environmental Studies programs may also find the film to be a noteworthy depiction of the human losses that stem from pollution and natural resource exploitation.

Awards:Grand Prix, Festival International du Film Documentaire Océanien (FIFO); Grand Jury Award, Guam International Film Festival; Golden Sun, Suncine Environmental Film Festival; Grand Prix Rigoberta-Menchu, Festival International Presence Autochtone

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.