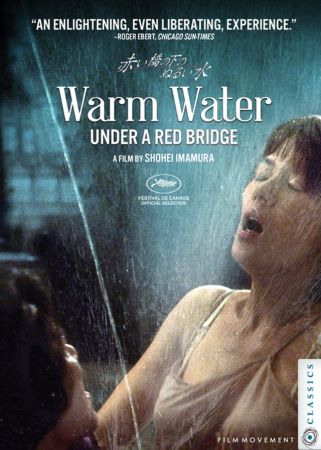

Warm Water Under a Red Bridge 2021

Distributed by Film Movement

Produced by Hisao Iino

Directed by Shôhei Imamura

Streaming, 119 mins

General Adult

Japanese Studies; Sexuality

Date Entered: 09/07/2023

Reviewed by Andy Horbal, Cornell University LibraryFilmmaker Shôhei Imamura’s career spanned five decades, beginning in the 1950s as an assistant to legendary Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu and continuing until just a few years before his death in 2006 at the age of 79. During this time, he won two Palme d’Or awards at the Cannes Film Festival, making him one of only ten (if we count Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne separately) directors to earn this prestigious honor more than once, alongside numerous other accolades. As per the title of a 1995 documentary directed by Paulo Rocha for the French television series Cinéma, de notre temps, he was a “free-thinker” whose works span a wide range of genres, eras, and styles, but he is perhaps best known for his frank depictions of greed and lust and strong (if rarely exactly “noble”) female characters.

Warm Water Under a Red Bridge, Imamura’s final full-length film, features many of his trademark themes and techniques. As befitting one of cinema’s most tireless experimenters, it also finds him breaking new ground. The movie begins with the discovery of a dead body. Taro (Kazuo Kitamura), known to his fellow inhabitants of a Tokyo homeless encampment as the “blue tent philosopher” in a nod to his fondness for “difficult books,” has passed away leaving behind little more than a story about a treasure (a gold Buddhist statue) that he secreted away years earlier in a house on the Noto Peninsula. With no better prospects, the recently unemployed salaryman Yosuke Sasano (Kôji Yakusho) decides to go look for it. With the aid of an old woman (Mitsuko Baishô) he finds waiting next to the red bridge of the film’s title, who silently points the way, he discovers the house just where Taro said it would be. Just then a younger woman (Misa Shimizu) emerges from within.

Up until this point, about 15 minutes into the film, the only indication that anything odd is afoot are the haunting glissandos and jaunty horns of longtime Imamura collaborator Shinichirô Ikebe’s score. This all changes when Yosuke spots the younger woman, whose name we will eventually learn is Saeko Aizawa, at the grocery store standing above a pool of water and rubbing her legs together. As he watches, she surreptitiously slips a piece of cheese into her purse and walks away. He plucks a fish-shaped earring out of the puddle and follows her back to the house to return it. Inside he finds Saeko living with the older woman, who it turns out is her grandmother and who is senile (she thrusts one of the fortunes she spends her days writing, thinking the local temple is still paying her to do so, into his hands). Saeko takes Yosuke upstairs and feeds him the stolen cheese, which she appears to find erotic, with ice. In between bites she tells him that he must never tell anyone about the water. They kiss and begin to have sex. Saeko says that she is embarrassed by the water, which is “cold, hot, and it feels so good.” As they make love in a long shot framed by a window with a beautiful view of the Tateyama Mountain Range across the Sea of Japan, a geyser erupts out of Saeko as she climaxes, soaking Yosuke and the room as she cries “the water!”

Yosuke is clearly more turned on than disgusted, and the rest of the movie chronicles his journey toward realizing that Saeko is the “treasure” he has been seeking his whole life. Her confession that she tried to kill herself many times because of her condition and the accusation that Yosuke’s wife (who we only hear over the phone and who divorces him about two-thirds of the way through the film) levels at him that he gets confrontational when he’s challenged connect them to other Imamura characters driven to extreme acts by desperate circumstances. Similarly, a black and white flashback sequence which shows Saeko’s mother drowning during a religious ceremony looks like it was pulled straight from one of the director’s 1960s films. The scene which precedes this one represents something different, though. Saeko and Yosuke tour a cavernous research facility designed to “observe neutrinos which are generated by the collision of cosmic rays and air through 50,000 tons of super pure water.” Afterward she informs him that it sits on the same site where a factory that discharged cadmium into the local river causing a disease called “Ouch Ouch Syndrome” was located. This is what Saeko’s mother was trying to cure someone of when a man disgusted by her “stupid superstition” interrupts her, ultimately leading to her death. “I expected the 21st century to be different,” Saeko says, “but nothing's changed.”

At first blush, Imamura seems to be suggesting that the turn of the millennium isn’t any more likely than other historic events he chronicled like the collapse of the Edo shogunate in the 19th century and the end of World War II to materially impact the lot of Japan’s working class. This is belied, however, by the beauty of the “Cherenkov Light” generated when neutrinos collide with the research facility’s body of water, Saeko’s delight at the way it links her and Yosuke to “the far ends of the universe,” and the optimistic conclusions of this film and 1997’s The Eel. It’s as if after a lifetime of showing respect for the ability of human beings to endure even the most unthinkable tragedies, Imamura wanted to cap off his oeuvre by celebrating these survivors.

So it is that the beautiful and weird final shots of Warm Water Under a Red Bridge feel almost like a parting toast. To Saeko and Yosuke, who finally consummate their union in a scene strikingly set amidst giant concrete triangles which ends with a rainbow shining through the mist of Saeko’s water, and to Saeko’s grandmother who dies at peace after finally finding out what happened to the lover (who turns out to be Taro) she was waiting for at the beginning of the film, just as she had every day of her declining years. To those who eschew religious and scientific explanations of life’s mysteries, and to those who lose themselves in them. Few of Imamura’s films are actually as bleak as they seem: although many end in death and/or madness, it’s usually also identified as an escape. With Warm Water Under a Red Bridge, an essential addition to any Japanese cinema collection, Imamura seems to be clarifying that these are even more accurately interpreted as moments of transcendence.

Awards: Best Actor (Kôji Yakusho), Chicago International Film Festival

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.