Rojek 2022

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Zayne Akyol, Sylvain Corbeil, and Audrey-Ann Dupuis-Pierre

Directed by Zaynê Akyol

Streaming, 127 mins

College - General Adult

Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS); Middle East Studies; Political Philosophy; Prisoners; Religion; Terrorism

Date Entered: 01/04/2024

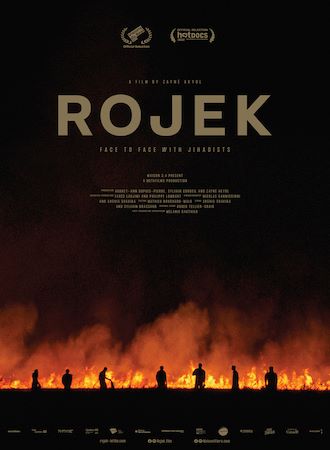

Reviewed by Michael Pasqualoni, Librarian for Public Communications, Syracuse University LibrariesNear the closing moments of Zayne Akyol’s Rojek, a silhouette of a man at night appears on screen, pacing and gazing at his cell phone in the face of the brilliant flames of a wildfire, suggesting a metaphor inherent within the film about the tensions any civilization navigates between modernity and other elemental forces of conflict and spiritual dogma. Canadian director Akyol is Turkish born to Kurdish parents, prior to relocating to Canada as a child, and with Rojek, she presents an important, and at times disorienting glimpse of former ISIS fighters imprisoned in Syria. This is a well-done film, despite its disturbing subject matter (i.e., religion in its extreme editions seen as prone to morphing into a death cult). We meet fifteen imprisoned former members of ISIS, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [aka: Daesh], both men and women, who speak to the viewer through extended accounts of what led them to join that terrorist organization, their devotion to specific interpretations of the Islamic religion, and moving testimony describing the rooted nature of fears, dreams, and loyalties to their families and faith.

Rojek mixes the direct address to the camera of these orations with shots of dusty Syrian terrain and sweeping aerial flyovers of bombed out cityscapes and lonely detention camps. These are fashioned as an apocalyptic visual tone poem. An original score by Roger Tellier-Craig adds a superb element of dread. The film is not an easy viewing experience, because it does ultimately arrive at images of killing, and repeated descriptions of the sentiment driving those individual and collective actions as arising from religious zealotry. Some may react negatively to these incarcerated fighters being given so much unfiltered time to address the camera. Interpretation of what they choose not to share is as valuable as what is spoken, with Rojek also fairly seen as an extended cinematic meditation on the wider nature of guilt and justice.

Akyol succeeds in her film in centering persons over places. The emphasis here is not on elaborate timelines or scholarly analysis of broader tactics or policies of governments, insurgent forces, or their leaderships. The film’s objective is not to be a general definitional survey text spanning recent and deeper background narratives for the wider history of conflicts in Syria or the history of ISIS. Rojek does not set out to be an academic treatment of those geographies, governments, personalities, or religions, despite a variety of these players and stakeholders being mentioned by the prisoners whom we meet. Akyol gives the viewer a document of average human beings who were deeply committed, and some still, to objectives of ISIS and specific interpretations of Islam undergirding that terrorist organization and its conflicts. In allowing the prisoners to speak at length, a great deal of diversity is apparent from these detained men and women. By the wrap-up of the film, one recognizes their respective conclusions on the wisdom and folly of past choices is far from monolithic.

Cinematographic qualities in Rojek often match such objectives delving into the prisoner’s perspectives, employing a frequently claustrophobic shooting style, cutting from confined prison corridors to traffic jams at military inspection checkpoints, and back to the narrower head and shoulder, confessional shots of the detainees. At no point are the female interviewees associated with Daesh ever viewed without face coverings. While only on screen briefly, the mood shifts dramatically when the focus changes to coverage of Kurdish military forces, some of those troops are all female. Across clearly sympathetic framing of military units who have put down terrorist groups like Daesh, and who hunt any number of extant ISIS sleeper cells, tacit observational commentary invites us to consider the humanity of victims and combatants on all sides.

Both inside and outside the prison cells is an omnipresent feeling of control, surveillance, regulation, and danger, applicable to those fighting to maintain democracy and to those who see democracy as a false God. The film is refreshingly free of expert lectures or explanatory narration on the audio track. The filmmaker’s own voice is heard only infrequently, including in an interesting self-reflexive audio clip during one of the female prisoner testimonies, where Akyol is comfortable revealing a willingness to include that interviewee in the editing choices for how that prisoner will be represented. The intent is not to force feed any critical analysis of what these detained terrorists verbalize, and in yielding to more silent forms of viewer contemplation, Rojek remains a critical work, nonetheless.

Akyol intercuts a stark visual lyricism with the prisoner testimonies and glimpses of Syrian Democratic Forces, as the viewer backs away from the confinements of prison hallways and detention cells, into a variety of aerial drone shots and outdoor, sometimes slow-motion landscape and streetscape images, including vivid wildfire footage. As one reaches the end of the interviews, and some unflinching depictions of religious intolerance, various brutal killings, or ideological re-education efforts of Daesh, including use of propaganda techniques that employ streaming video technology, the fire lines we often see from above separating charred from untouched fields conclude an array of other visual metaphors Akyol presents.

Fire divides barren from fertile lands. Fuel that is both liquid and in flames reminds of creature conflicts well prior to human dominion. Wandering children and livestock traverse buildings constructed, and more often than not crumbled into ruins. Some prisoners are rhapsodic in their descriptions of Jannah ("Paradise"), as we often see in Rojek worldly surroundings that seem entirely unlike those loftier visions. There is a poetic contrast in the comparison of some of the vast landscapes with the frequent depictions of prisoners, vehicles, and soldiers moving in single file. Much like the first filmed images of Earth from outer space, Akyol’s wider establishing landscape and aerial cinematography invites the viewers of this documentary to consider these uncomfortable questions of war, religion, life, and death in the context of the wider purposes of humanity on the fragile planet that we all share.

Awards:Visions du Réel 2022; Directors Guild of Canada Special Jury Prize, Hot Docs 2022; New Voices Award, Gimli International Film Festival 2022; Nouvelles Vagues Acuitis Award, The La Roche-sur-Yon International Film Festival 2022; Second Prize, Seminci Valladolid International Film Festival 2022; Best Cinematography, MIRAGE – Art of the Real Festival 2022; Best Film Testimony (Special Mention), Ji.Hlava International Documentary Film Festival 2022; Artistic Expression Award, MedFilm Festival 2022; Jury’s Grand Prize, Festival International du Film Politique de Carcassonne 2023; Jury Award, Docville International Documentary Film Festival 2023; Special Jury Award, EBS International Documentary Festival (EIDF) 2023

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.