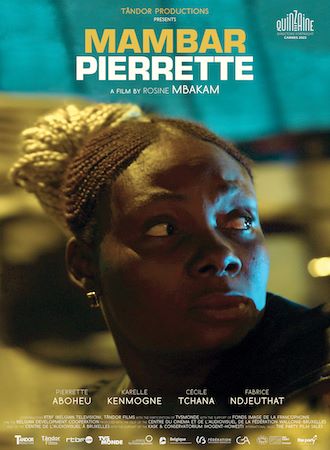

Mambar Pierrette 2023

Distributed by Icarus Films, 32 Court St., 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; 800-876-1710

Produced by Geoffroy Cernaix and Rosine Mbakam

Directed by Rosine Mbakam

Streaming, 93 mins

Middle School - General Adult

Cameroon; Entrepreneurship; Women's Health

Date Entered: 01/09/2024

Reviewed by Andy Horbal, Cornell University LibraryMambar Pierrette begins with its eponymous Cameroonian heroine (Pierrette Aboheu Njeuthat, who you’d never know is not a professional actor) tending a cook fire and preparing a meal. Importantly, we also see who this work is for: her infirm mother (Marguerite Mbakop), who says, “if I was feeling well, I would have helped you.” This scene is mostly shot with a handheld but steady camera, as are the ones that follow which depict Mambar helping her son (Duval Franklin Nwodu Chinedu) deposit coins into a moneybox, buying fabric and other supplies for her sewing business, and interacting with clients who deeply appreciate the clothes she makes for them (“wow, Mambar,” one says upon trying on a dress), even if no one seems to be able to afford to pay full price. Mambar’s willingness to settle for whatever they can afford is explained in part when her sewing machine breaks and she is able to get it fixed for a quarter of the rate the repairman she addresses as “Papa Ema” (Emmanuel Keutagna) originally quotes her because that’s all she has. It also obviously matters to Mambar that her labor isn’t in the service of anonymous customers, but members of a community whom she knows well.

Although this is director Rose Mbakam’s debut narrative feature, she has a number of non-fiction films under her belt and her documentarian’s eye for detail serves her well. The close-ups of Mambar’s hands and face as she marks vibrantly-colored patterned fabrics with chalk, threads needles, and irons are a joy to watch, which makes it immensely frustrating when misfortune begins piling up and threatens to keep her from this valuable, pleasurable work. First Mambar is robbed in a scene which Mbakam has explained is deliberately underlit because she is “not a voyeur.” Then a flood destroys the school supplies Mambar bought for her son, forcing her to use the money he has been saving for a backpack and shoes to purchase more. She spends the next morning scrambling to raise additional funds, including by reporting her deadbeat husband to social services over her mother’s objections, only to return to her shop to find that it too has flooded.

Viewers new to Mbakam’s work may worry that the film is spiraling into miserabilism when Mambar appears to discover that on top of everything else, her sewing machines have been stolen. Others may have noted that the previous scene in which the offscreen social worker (Evelyne Baiba) Mambar talks to scolds her (“Madam, it’s not right to stay with a man and have three children when you’re not married”) is shot from that person’s point of view. This recalls Mbakam’s contribution to the collaborative essay film Prism, which contains an interview that references film critic Serge Daney’s argument that everything which happens in front of the camera is in the Global South, while the camera itself is always in the North. Sharing too many details about what actually happened would risk spoiling one of Mambar Pierrette’s most surprising and pivotal moments, but suffice it to say that Mbakam is very much in control of her material.

The final third of the film consists of Mambar taking part in or listening to a series of fascinating conversations. In one she visits an aunt (Cécile Tchana) who mentions that Mambar’s mother told her about the visit to social services but says “I can’t lecture you. It’s your life. You alone know what is right for you.” In another, she shares the story of how she fell out with her husband basically just by being independent and able to support herself. Falling asleep one night she overhears her mother explaining to her grandson that the reason she’s always ill is because a witch ate her heart when she was young and replaced it with that of a little boy. Finally, multiple people make a point of telling Mambar that the white-colored mannequin with unblinking eyes that stands outside her shop scares them. One, a street performer (Calvin Zognou) who laments the fact that art is dead in their country, addresses it and says, “you understand nothing.” Another neighbor (Léonce Sonia Bangoub) notes that it frightened her mother so badly in the middle of the night that she instructed her son to remove its head and hide it in the kitchen until morning. Mambar simply laughs in response, then goes back to work in what turns out to be the film’s final image. Although Mbakam’s use of symbolism is far too nuanced to be reduced to a single thesis statement, the general point seems clear enough: outsiders are free to watch and encouraged to help, but should never make the mistake of presuming that their presence is either necessary or inevitable.

Rosine Mbakam is not yet a household name, even in film circles, but she’s a talented director who works with themes like colonialism and representation that loom large in academia and the public discourse. Although libraries may not currently be inundated with requests for her movies, they are likely to be of interest to many scholars and other viewers. Mambar Pierrette is thus highly recommended to anyone who wishes to develop their collections in these areas or stay ahead of the curve.

Awards: Cannes Film Festival 2023, Director’s Fortnight Premiere

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.