Shtetlers 2020

Distributed by Film Movement

Produced by Katya Ustinova and Aleksandr Zavalishin

Directed by Katya Ustinova

Streaming, 80 mins

High School - General Adult

Anthropology; Jewish Studies; Soviet Studies

Date Entered: 07/25/2023

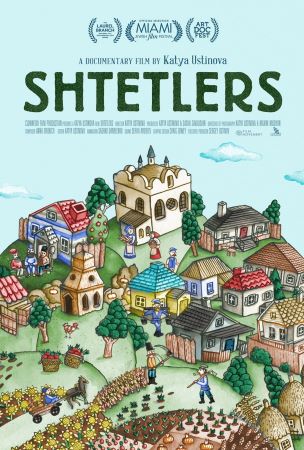

Reviewed by Michal Goldman, Documentary Filmmaker; Member-Owner, New Day Films (https://www.newday.com/filmmaker/175)Shtetlers, by Katya Ustinova, offers us a series of interwoven portraits of mostly older people who grew up in “shtetlakh” – Yiddish for the thousands of small towns or villages in Eastern Europe where Jewish and Christian neighborhoods existed in close proximity for centuries. For the most part, these Jewish communities no longer exist: Jews began leaving them early in the twentieth century, and the Holocaust delivered the mortal blow. But some of the Jewish communities in the Soviet Union continued into the 1970s: Ustinova’s film focuses on shtetls in Ukraine and Moldova. Charming black and white animation provides a schematic introduction to the economic interdependence between the shtetl’s Jews, who mostly operated small businesses or were professionals, and its Christians, who mostly worked in agriculture. Beautiful footage from the Russian archives sketches the historical context.

This film does not look closely at the history of the shtetl or its sociology. The picture the film paints of communal life is simplistic, generalized, and maybe a bit romanticized. The historical context provided is minimal – just enough for the viewer to make sense of the story.

Instead, from its title onwards, the film delves into how people who grew up in these places have carried that experience of place with them, whether they have stayed relatively close to home or migrated to other continents. The film explores in detail the shtetl as it lives on in these people’s bodies: in their customs, language, and music; in their food, their humor, and even their physicality – the way they walk, their gaze, the timbre of their voices – as well as their specific memories. The young Russian-born filmmaker, often working alone as a crew of one, drew close to these much older people, filming them beautifully and tenderly. She gained their trust, often because they had already met people doing research for a new museum about the shtetls of the Soviet Union founded by her father. The result is a filmed portrait of shtetl life that is so evocative you almost taste it, while at the same time you feel that this way of life is gone forever.

The Orthodox Christian neighbors whom Ustinova chooses to film were deeply, and perhaps atypically, engaged in the lives of their Jewish neighbors. Maybe for that reason, or maybe just because of the more general cultural proximity and sharing of shtetl life, they too carry the Jewish shtetl within them and evoke it as powerfully as the Jewish “shtetlers” do. The film is at once an elegy for a way of life and a celebration of the active, formative connection between Christians and Jews this way of life inspired, a connection that goes way beyond coexistence.

The film begins with a long sequence following Volodya Malishevsky, an Orthodox Christian man in his 70s, as he shows the filmmaker the now-abandoned Jewish part of the town where he still lives. His stories about the former occupants of these ruined houses – the baker, the tailors, the sausage maker, the hairdresser, the woman who sold sparkling water by the glass – give us a sense of the economy of the place when it was a functioning community. Volodya also shows us the Jewish cemetery, where he tries to keep the tall grass from over-running the tombs.

The Orthodox Christians portrayed in this film emerge as caretakers of Jewish spaces and communal memories. It would be interesting to pair Shtetlers with Simone Bitton’s beautiful film Ziyara, which looks at the Muslim caretakers of Jewish religious spaces in Morocco after the Jews themselves have gone elsewhere. What can these films tell us about the way we bear witness to each other, sometimes in the larger context of mutual prejudice and open, even explosive, hostility? Some of the Muslim caretakers in Ziyara, and some of the Orthodox Christians in Shtetlers, seem to feel a bit abandoned by their Jewish former neighbors who have moved on. Some are paid by the absent Jews to take care of the places where they once lived or prayed. Some feel blessed and grateful for the connection.

In this regard, the scene in Shtetlers that fascinated me the most takes place in Chernivtsi (Czernowitz,) which is not a shtetl at all, but a city in Ukraine where there is still a small Jewish population. Noikh Kafmansky, an elderly Jew with a long white beard, is the rabbi of the beautiful old synagogue there, one of two in this city. A few elderly Jews come to pray in its small prayer hall where the walls are decorated with charming murals of animals and plants. Rabbi Kafmansky supports his synagogue by ministering to the many local Christians who come to him one by one seeking his practical advice and his intercessory prayers on matters of love, enmity, health, and success, leaving him a bit of money. As they leave, they kiss the mezuzah on his office doorway and then cross themselves. For them he seems to be at once a saintly figure and someone more knowledgeable about the wider world than they, and they see no contradiction in asking for his prayers.

For this viewer at least, this film raises questions that it doesn’t attempt to answer. Did shtetls in the Soviet Union survive longer because of a more integrated culture – one with less emphasis on religious practice under the Soviets? Or did Jews remain in these towns into the 1970s because it was so difficult to leave until American aid helped them to emigrate?

Shtetlers reminds us that human experience is first and foremost individual, and we should not generalize or abstract it before we’ve acknowledged and examined its vivid individuality. The vividness of this film makes an engaging introduction to the subject of rural East European Jewish life in the Soviet Union and beyond and hints at the complexity of that life. The filmmaker’s exploration of the cultural and economic interpenetration between two religious communities gives Shtetlers its emotional depth and would make this film useful to any anthropologist, historian or sociologist who is considering that subject, whether in rural or urban communities.

Awards: Jewish Spotlight First Prize, Rhode Island International Film Festival; The Laurel Branch Award for the Best Debut, Artdocfest, Russia

Published and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Anyone can use these reviews, so long as they comply with the terms of the license.